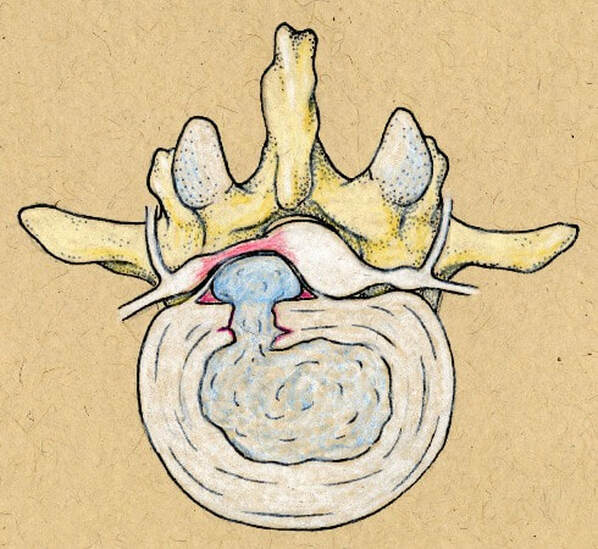

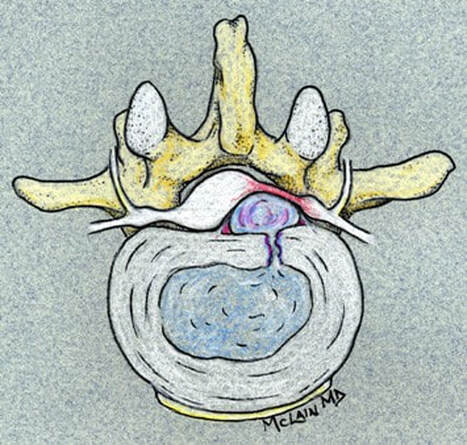

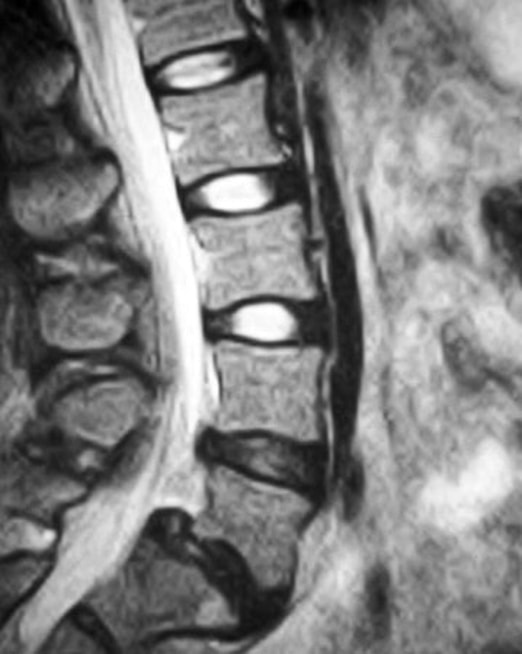

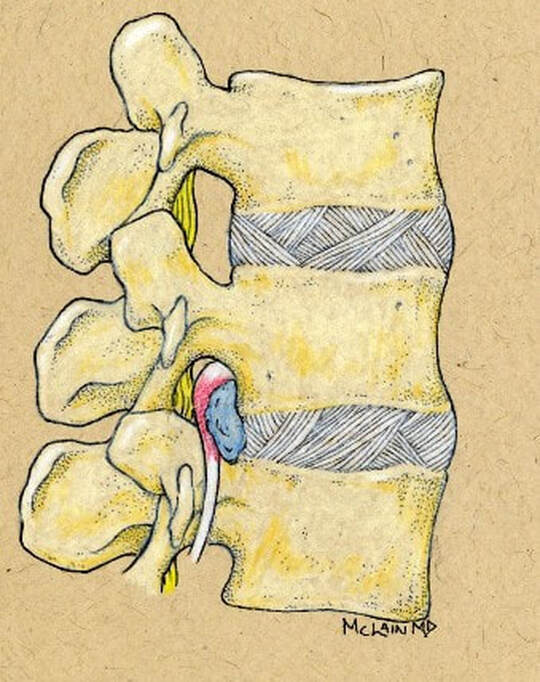

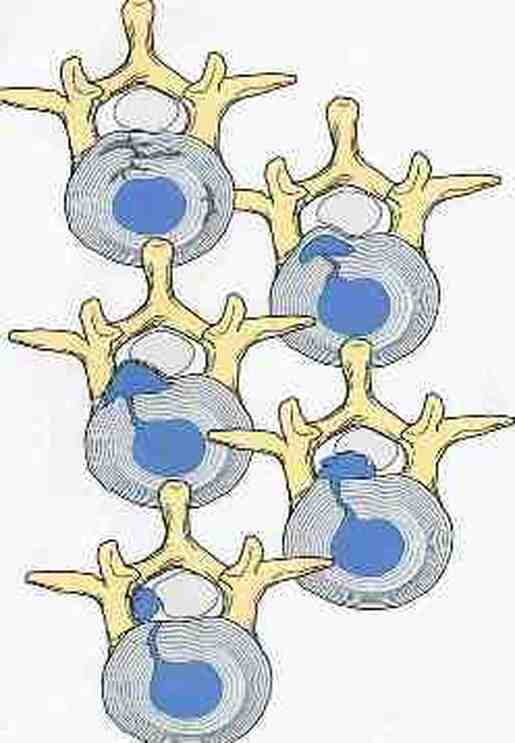

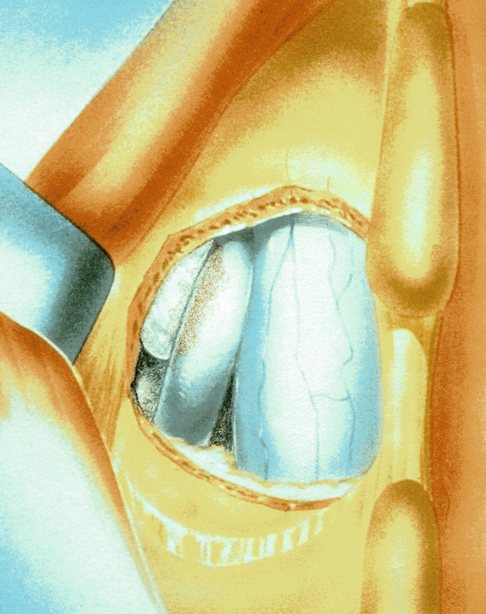

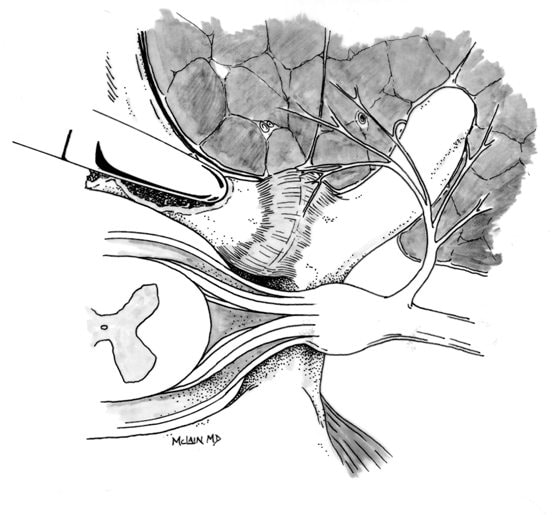

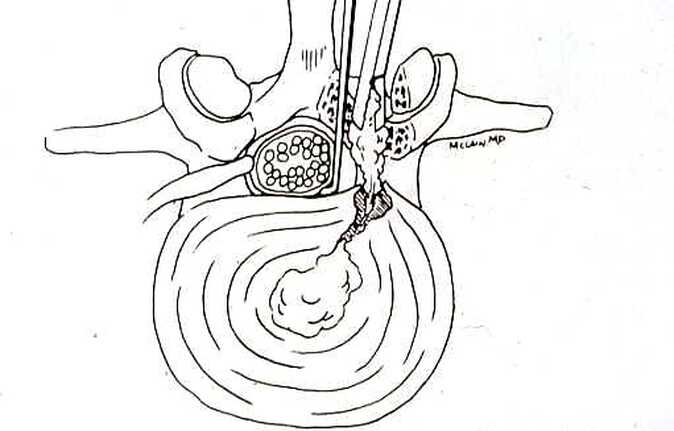

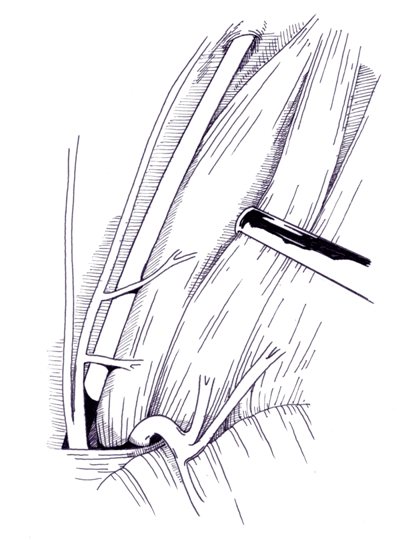

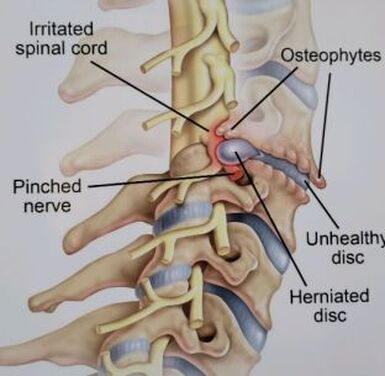

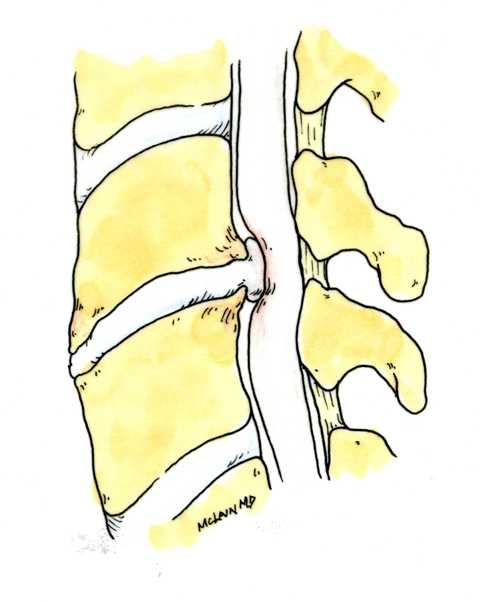

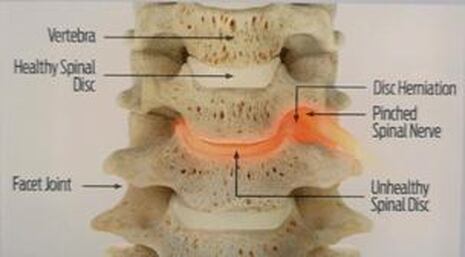

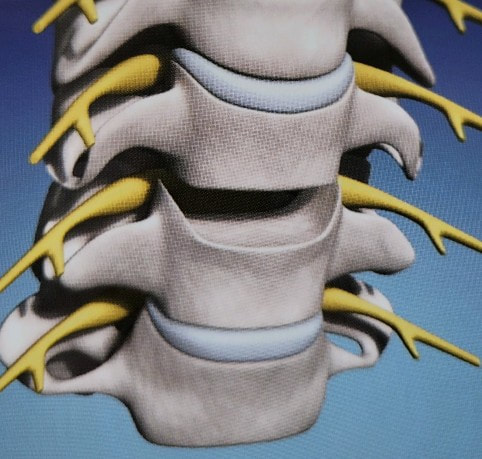

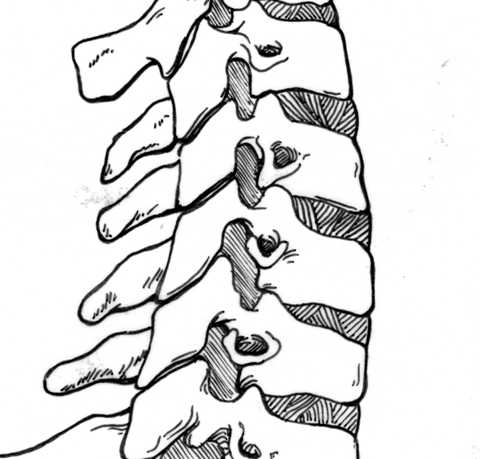

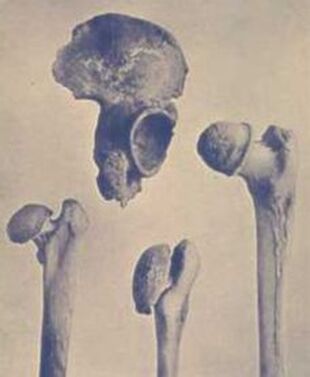

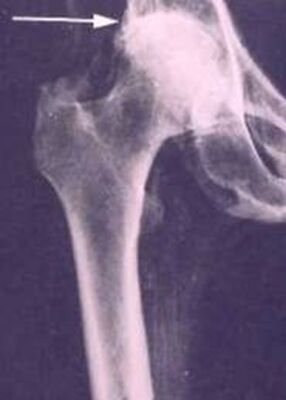

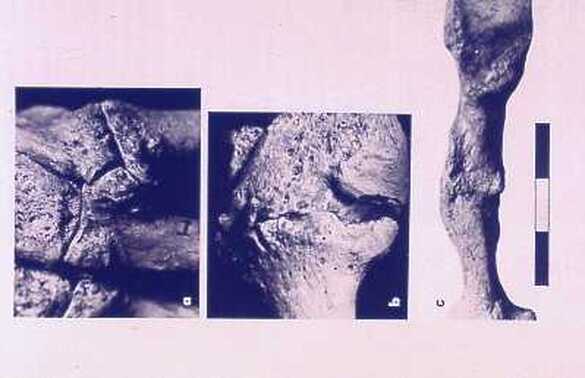

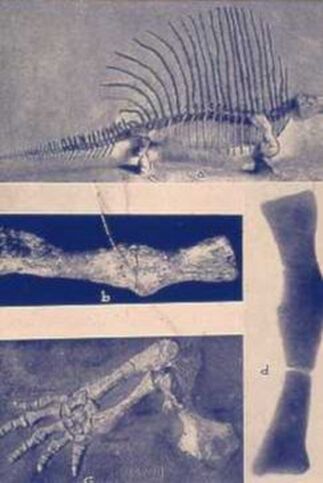

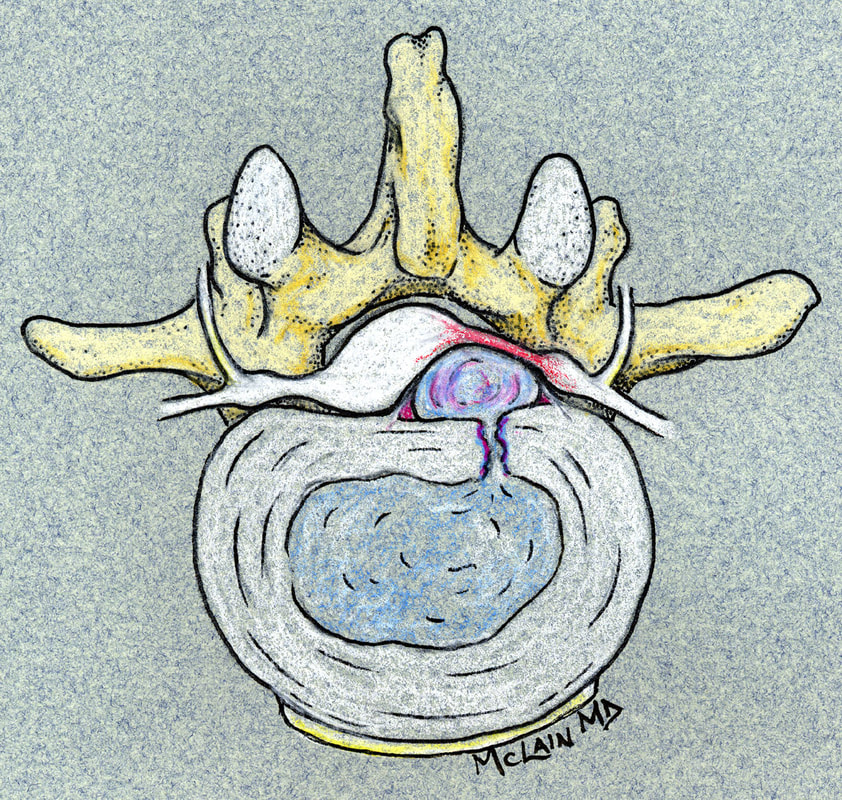

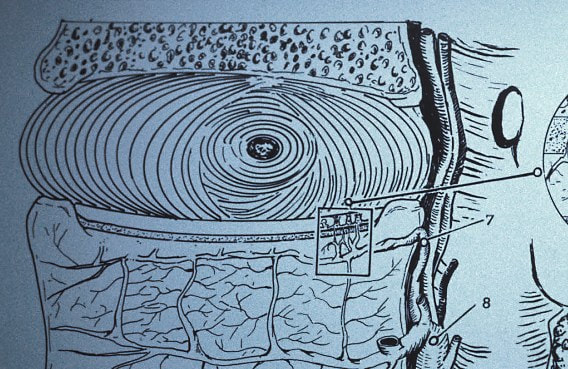

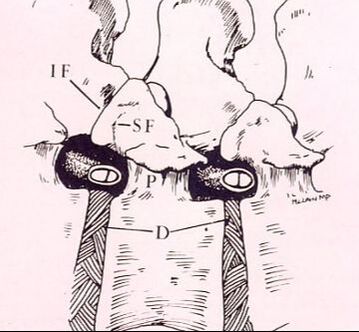

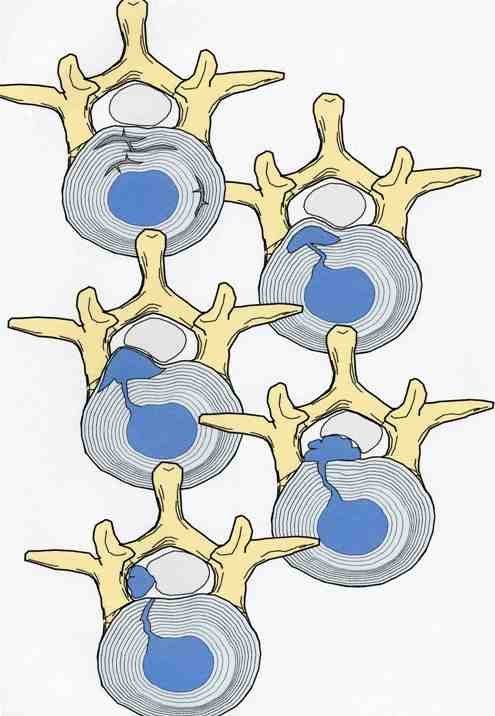

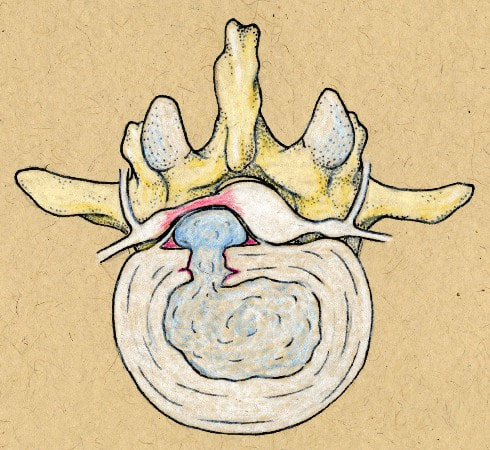

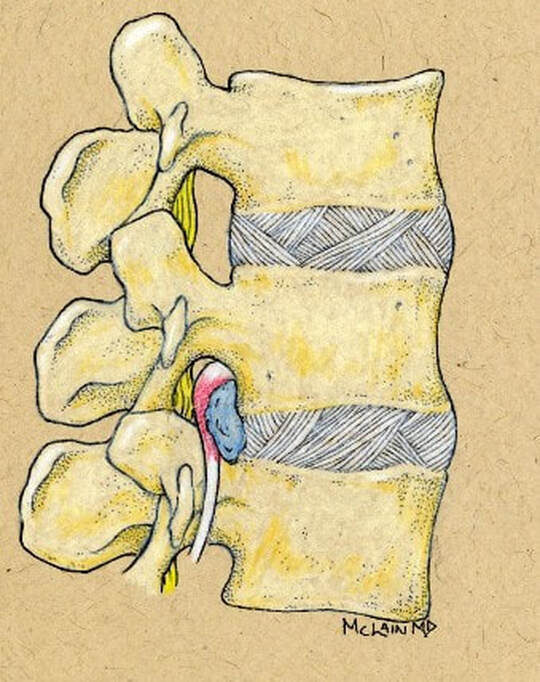

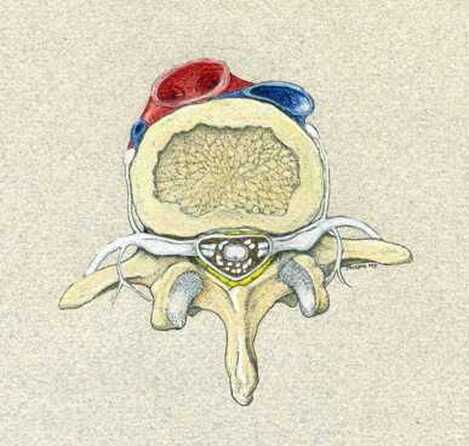

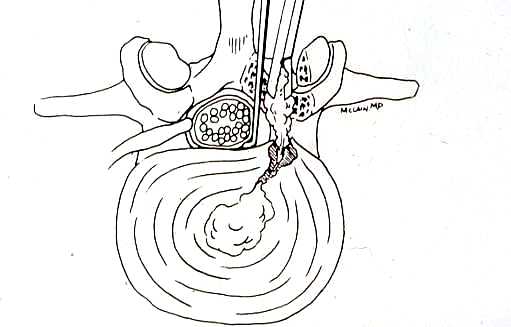

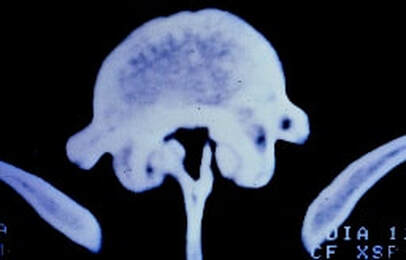

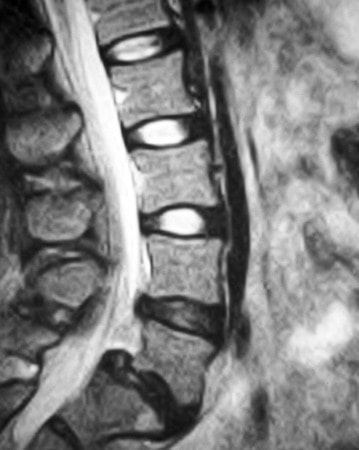

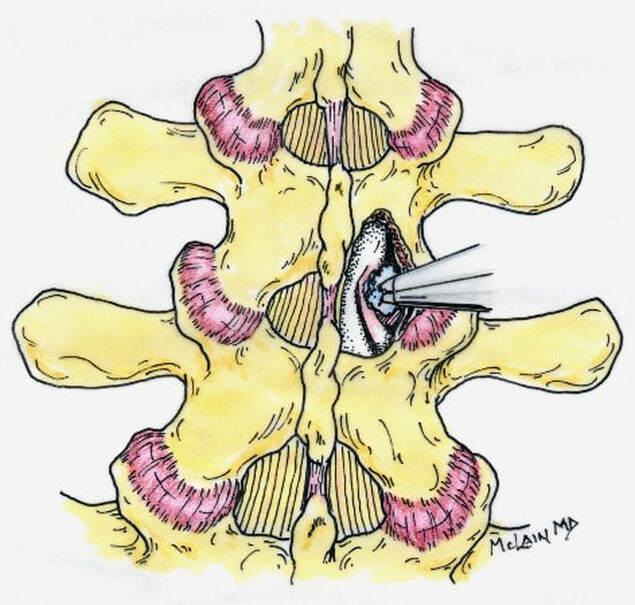

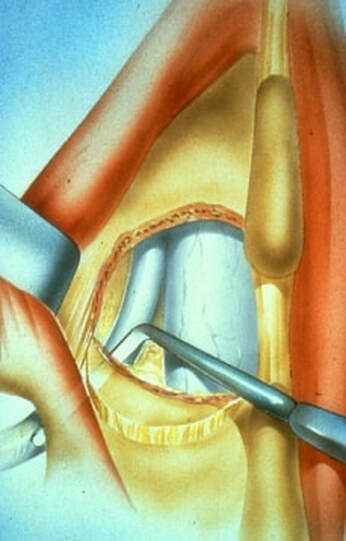

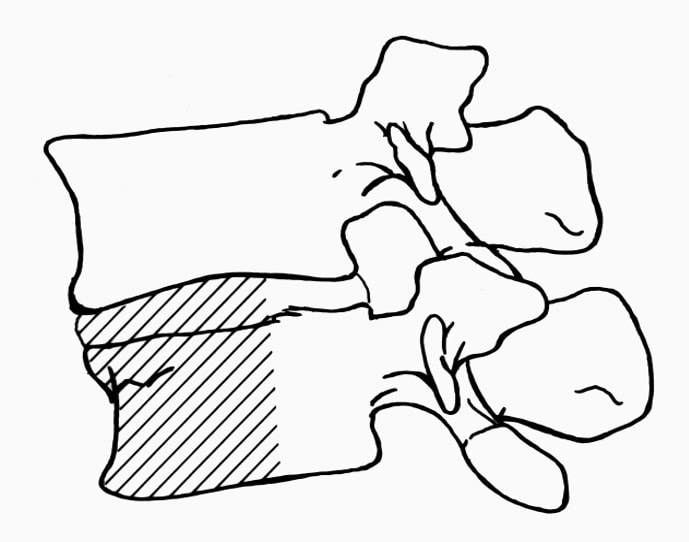

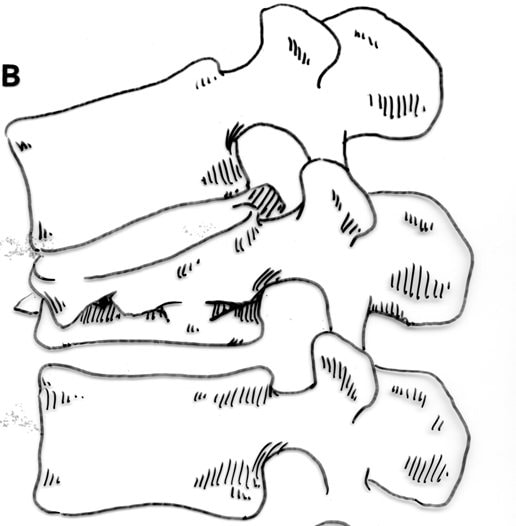

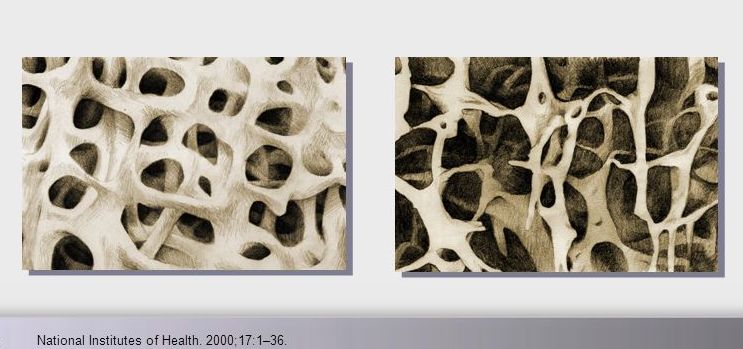

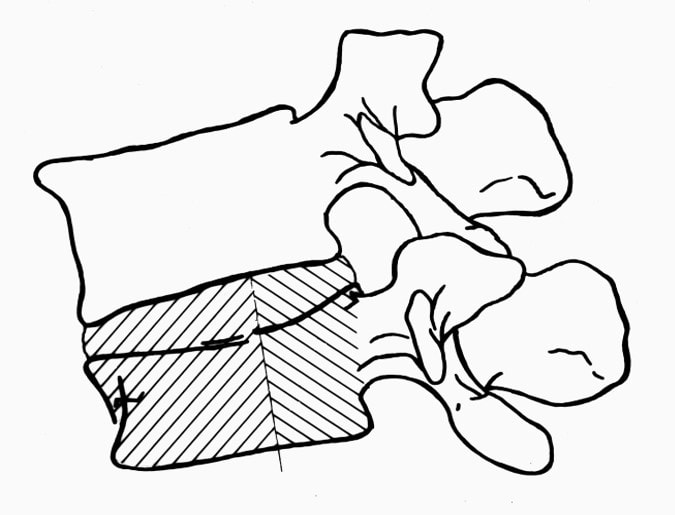

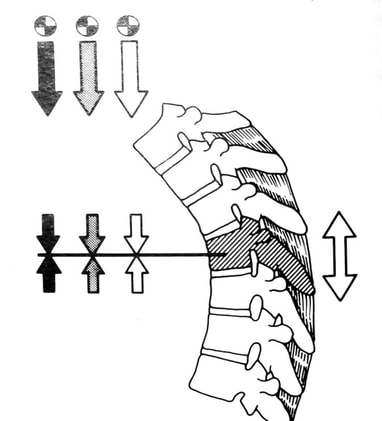

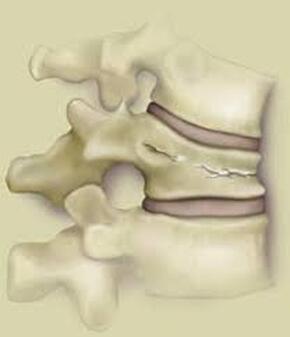

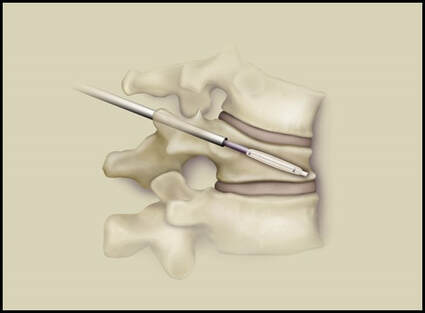

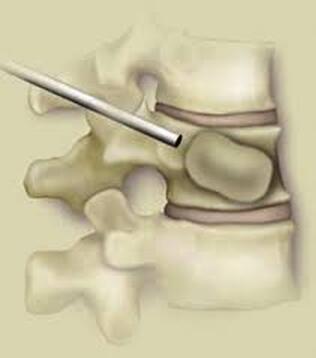

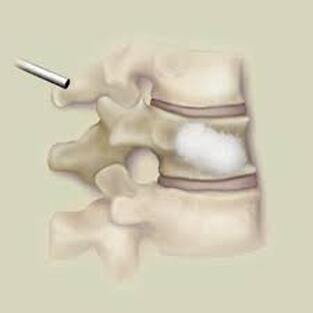

Next in my series of ten common problems - Lumbar Disc Herniation and the leg pain, or radiculopathy, that often causes the most frightening concerns.Lumbar Disc Herniation is a common cause of back and leg pain, presenting in different ways and with different degrees of intensity. Potential for recovery is actually quite good, but varies from patient to patient depending on size of the protrusion, size of the spinal canal, the patient's age, their activity level and functional demands, and the extent of the disc disruption associated with the herniation. That's alot of variables, and means that your neighbors disc herniation was probably different than yours, and their experience - the symptoms, treatment, and recovery - may be very different as well. It's important to understand a little of the language used to describe disc herniations. Radiologists often use vague and descriptive terms to describe the herniation, ranging from "displaced" to "protruding", "bulging", "ruptured", all the way to "massive extrusion". When your primary doctor reads that report, it's not surprising that they occasionally over-react and translate to you that "your disc has exploded!" and that "you need surgery or you'll be paralyzed!" That's a pretty terrifying message, and it's almost never correct. That's why getting an opinion from a specialist is often the best decision for a patient with a severely symptomatic disc herniation. The important point: different types of disc herniation may represent both a different stage of disc deterioration and a different indication for treatment. First of all, What is a Disc Herniation? Disc herniation is a term applied to a wide variety of disc disorders, and the terminology can be confusing. Discs can be described as herniated, slipped, ruptured, bulging, protruding, disrupted, and more. The size of the disc can be described as massive, significant, focal, and others, and the terminology doesn't really get us closer to a treatment plan. What is more important is where the herniation is relative to the nerve roots, how big it is relative to the spinal canal, and whether is a bulging disc, an extruded disc, or a sequestered fragment - a chunk of disc that has detached from its disk space and gotten lodged - like a stone in your shoe - in a spot where it is compressing a nerve. The lumbar disc is made up of two parts. In the healthy disc, the vertebral endplates above and below, and the disc annulus hold the nucleus pulposus in place which preserves the internal pressure in the disc. When there is a disc injury or degeneration, disruption of the annular fibers can occur causing fissuring and degeneration, or cause a sudden traumatic rupture. Whether this disruption happens slowly (chronic) or suddenly (acute) an annular defect is created that lets the nucleus out.  The disc is made up of an annulus - the thick outer portion made up of layer after layer of tough collagen fibers, overlapping like the layers or belts of car tire, and the nucleus - the softer, inner matereial that works as a shock absorber and cushing when the disc is under a load. When young the nucleus is quite gel-like, but as we age it gets tougher, but can still be squeezed out of the disc under great pressure. A disc herniation occurs when the soft inner portion of the spinal disc - the nucleus - gets pressed out of position and starts to bulge through the tough fibrous layers of the outer disc - the annulus. In some cases this happens over years and we see a narrowed disc on x-ray and a broad bulging disc on MRI. In other cases the soft material squeezes out through a tear in those annular fibers and protrudes directly into the spinal canal, like tooth paste squeezed out of the tube. In this case, the disc material can touch the nerve root directly and irritate it as well as put pressure on it. When the annulus begins to fissure and slowly deteriorate, disc bulging or protrusion results. Although no disc material has escaped into the canal, the disc causes the remaining annulus to bulge or protrude beyond its normal limits, putting pressure on the adjacent nerve root. Since no disc material has escaped from the disc space, this is referred to as a contained herniation. Once fissuring or tears have extended through the full thickness of the annulus, there is nothing to keep the nucleus in place, and the pressurized disc material follows the “path of least resistance”. Fragments of nucleus, annulus, and/or endplate can escape the annulus. Such herniations are termed non-contained, as displaced nucleus has pushed through and exited from the annulus. The central position of the tougher spinal ligaments tends to direct fragments laterally where there is less resistance but direct contact with the spinal nerve. Disc fragments may remain trapped under the that ligament (subligamentous) or less commonly may come through the ligament (transligamentous) into the canal. As long as the displaced disc material remains connected with the remaining nuclear material within the disc, this protruding material is referred to as extruded. When that fragment “pinches off” and becomes totally detached from its point of origin it is considered sequestered. At that point, disc material can migrate up, down, or sided to side, making an MRI image crucial to successful surgery. There are many potential causes of a disc herniation: Lumbar disc herniation, medically referred to as a herniated nucleus pulposus (often abbreviated as HNP) can result from a number of different causes. In young, healthy folks, a specific lifting or twisting injury can cause a sudden (acute) HNP, while in older patients with a longer history of wear and tear, a herniation can occur with very little trauma, and can even happen while you are sitting at your desk! Common causes include:

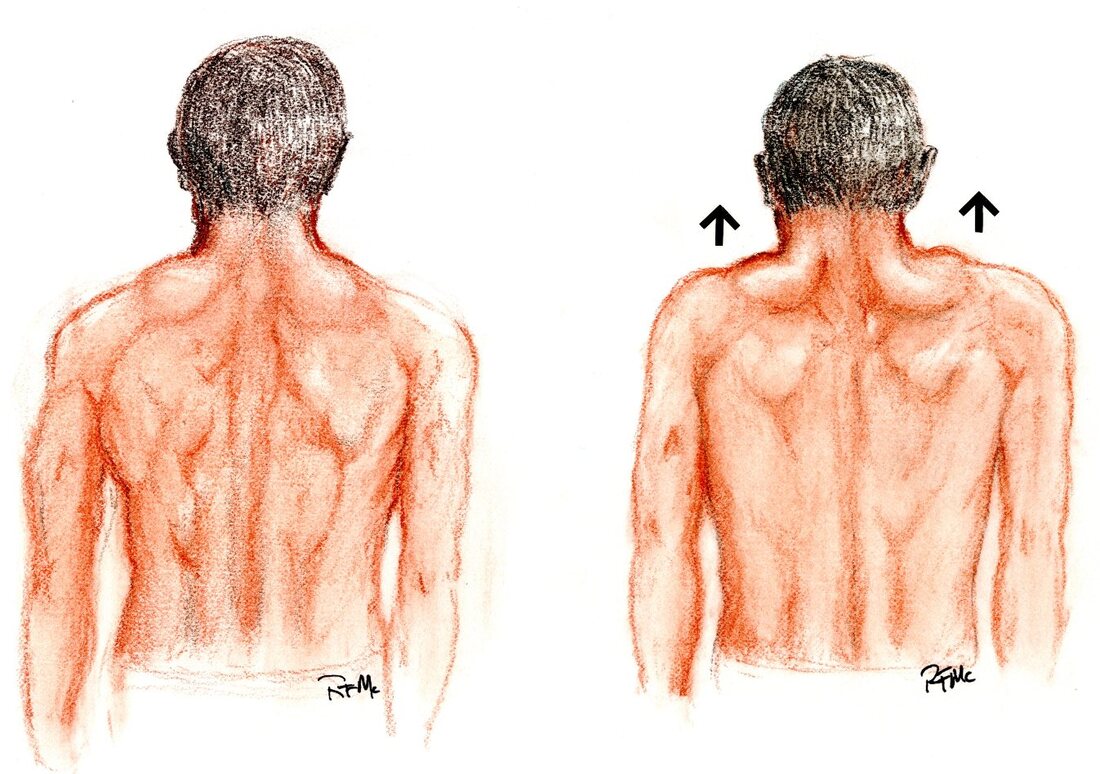

Genetics can play a role in your risk of disc herniation. Some families seem to be prone to herniation, and others - where the spinal canal is smaller than average - are prone to having severe symptoms when they do get a herniation. Overall fitness and health can reduce susceptibility to lumbar disc herniation and improve your chances of recovering without surgery, but this is a condition that can occasionally disable professional athletes. Understanding and practicing good body mechanics, maintaining a healthy lifestyle and body weight, and incorporating exercises to strengthen the core muscles can help reduce the risk of lumbar herniation and give you the best chance for recovery without surgery. So, What causes the pain?? The pain experienced after a lumbar strain is primarily attributed to the inflammation and damage to the soft tissues, including muscles, ligaments, and tendons, in the lower back. Back pain after a disc herniation can involve all of these, but the damaged or ruptured disc can also be a source of severe, deep-seated back pain. On top of that, and specific to disc herniation, irritation or pressure on the spinal nerve that is in contact with that disc can cause numbness and tingling, actual physical weakness, or severe - sometimes intolerable - burning pain in the leg, calf, foot, or toes. That is the symptom that most often brings patients to their local ER or doctor. Several factors contribute to the development of pain in lumbar disc herniation:

It's important to note that the severity and location/distribution of pain differs greatly depending on the level of the spine where the herniation has occurred. Proper treatment and management of the back pain - including rest, physical therapy, and anti-inflammatory medications - can speed the recovery process and alleviate back pain and muscular discomfort. If back pain persists or worsens despite therapy, there may be a more extensive injury or damage to other tissues, and further evaluation and intervention may be needed to return the spine to good function. The leg pain component can be treated non-operatively as well: this will typically start to get better in a week to three after onset, and should be much improved at six weeks. If symptoms are intense, if there is weakness associated with the pain, or the symptoms are not better in 6 weeks, something more may need to be done. Diagnosis:

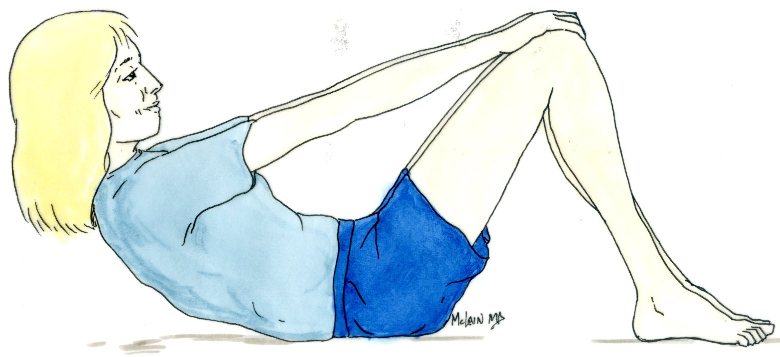

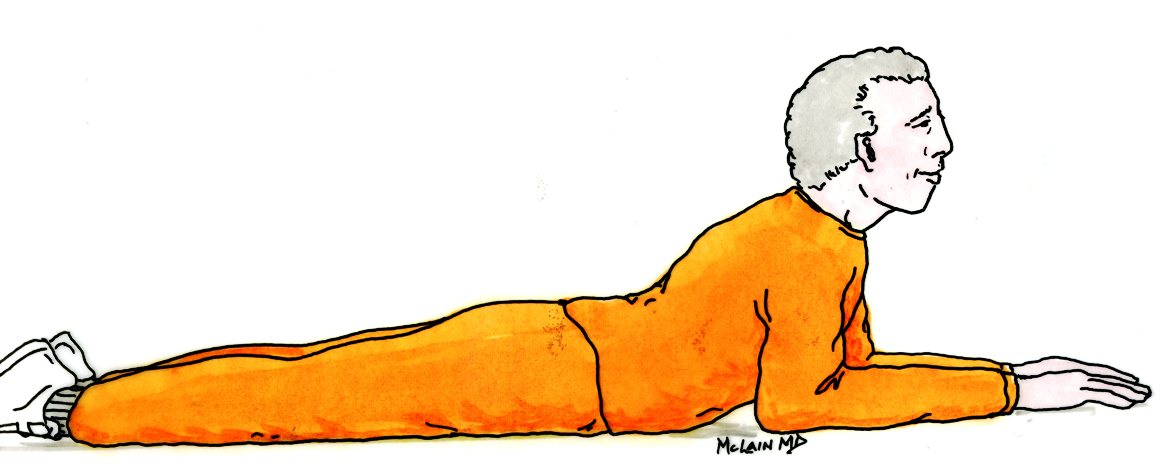

Treatment: Non-operative care: Most disc herniations causing severe leg pain ( radiculopathy) are successfully treated non-operatively. At least 90% of patients will get better with appropriate conservative care. Return to full activity, work, and recreation is usually possible, but takes time and requires appropriate medication and a course of active physical rehabilitation and exercise. Common non-operative approaches include:

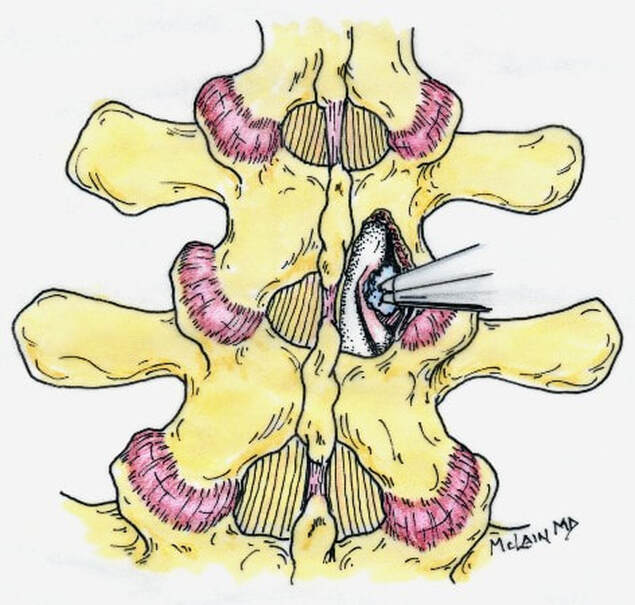

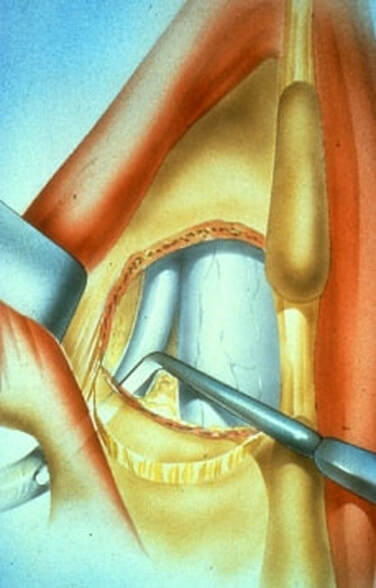

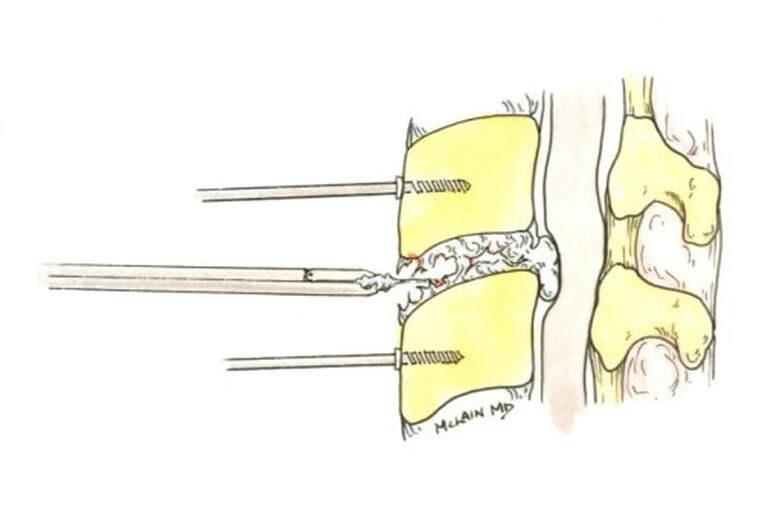

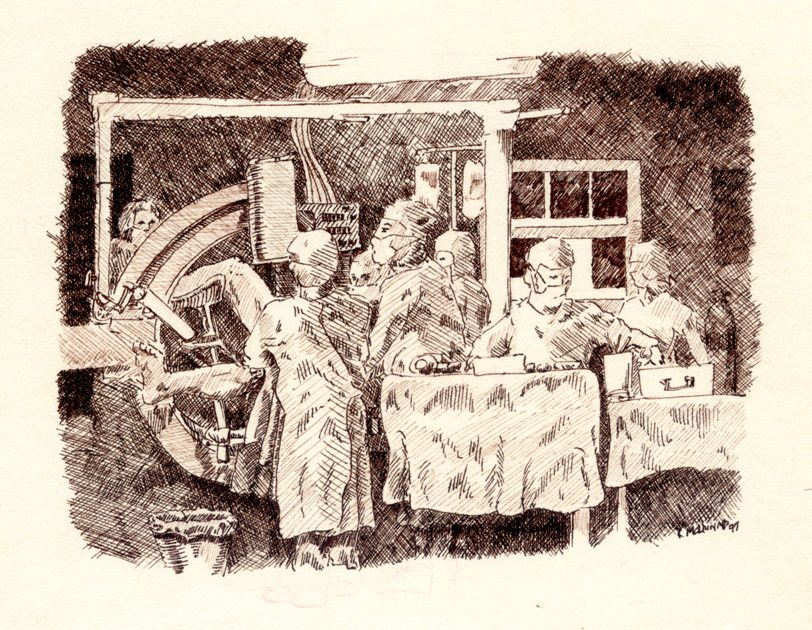

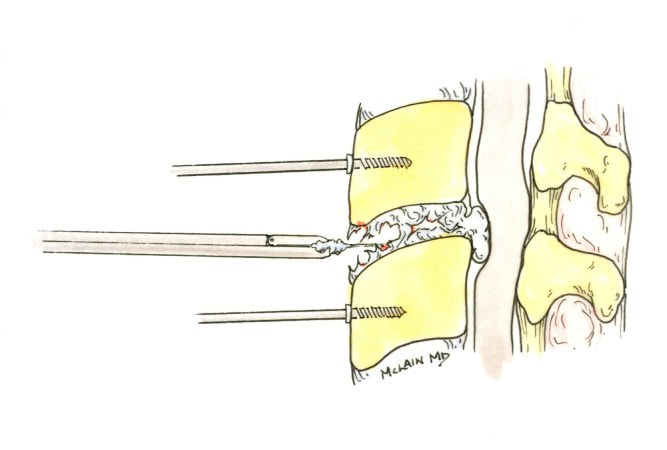

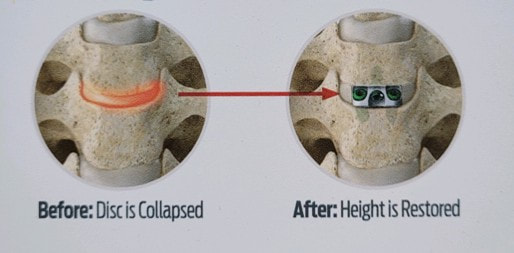

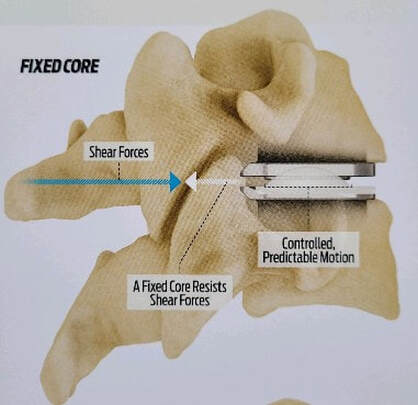

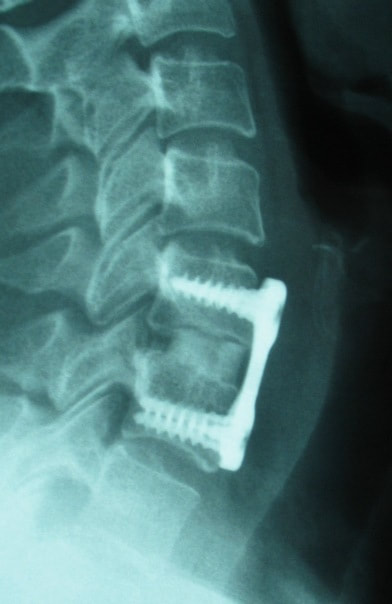

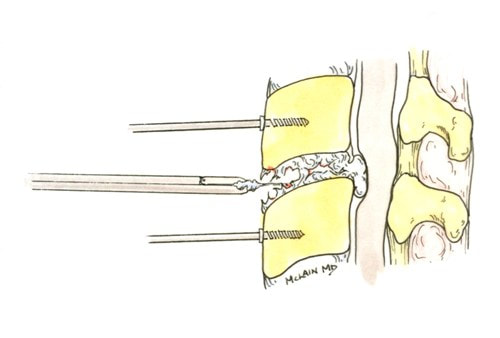

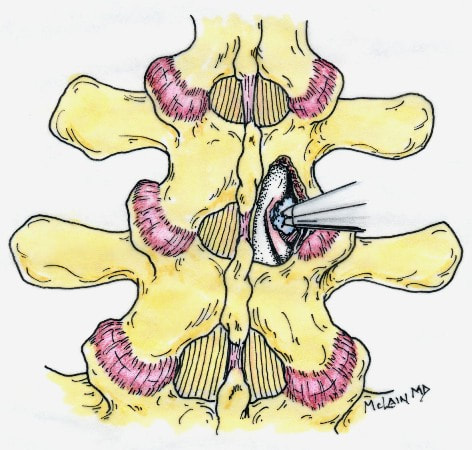

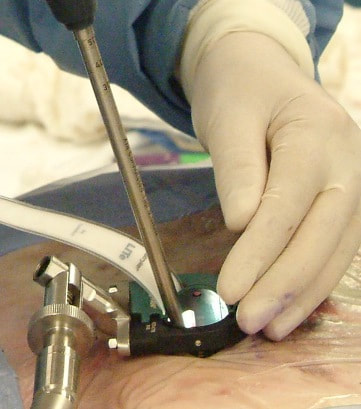

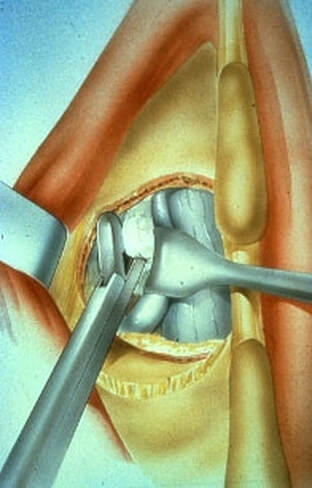

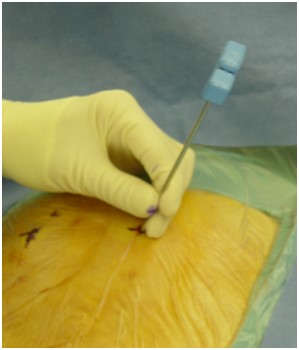

Surgical care: Surgery is generally considered only when conservative treatments fail, and the patient demonstrates evidence of a continued nerve compression and pain. Continued severe pain, neurological symptoms (such as persistent numbness or weakness), or evidence of a structural instability on x-ray imaging all suggest problems that may require surgical treatment. Surgical options include procedures that decompress the nerve roots, such as laminectomy or microdiscectomy (removal of part of a herniated disc), but more extensive procedures, such as spinal fusion, may be necessary if the structure of the spine has started to shift or collapse.

Healthcare Professionals: There are several kinds of healthcare professionals who can provide appropriate care and guidance after an acute lumbar disc herniation. The choice of provider may depend on the severity of your symptoms and the specialists available in your area, but should also take into account your own personal feelings about which kind of care you want to start with. Here are some of the professionals you may consider consulting:

Orthopedic surgeons and Neurosurgeons specializing in spine surgery can provide the same range of operations and procedures, with the same reliably excellent results.

Conclusion: The radicular leg pain associated with a disc herniation will usually start to improve on its own in the weeks after injury, and should be well tolerated by the end of six weeks. It can take quite a while for the back pain of a lumbar strain or sprain to completely heal, and the back pain aspect can be intense and limiting for weeks or even months after a severe strain. Because the back pain can be re-aggravated, patients may need to hold off of return to activity for a while after the leg pain calms down. With time and a good rehab program there is a great chance of getting back to normal activity without surgery. However, for those whose leg pain persists or flares every time they try to get back to work, surgical treatment may be necessary. The good news is that, for the majority of disc herniation patients, the surgery can be performed with a minimally invasive approach, requires a brief anesthesia time, and no hospitalization, and, if the disc fragment can be successfully removed from the canal, relief of leg pain and much of the back pain can be immediate! In any case, - with or without surgery - disc herniation is one low back problem that has a good prognosis for recovery and return to normal life.

0 Comments

Lumbar Back Strain: Understanding and Managing a Common, Painful InjuryI want to provide you with the important information you need to understand these common spine problems, the ones that patients most often ask me about. While specific medical advice about your problem should come directly from your healthcare professional, here is the next big concern in our list of ten spine problems that patients often ask about: LUMBAR SPRAIN AND STRAIN: Lumbar strain or sprain refers to an injury affecting the muscles, ligaments, or tendons in the lower back region, specifically the lumbar spine. These injuries are common and often result from overuse, improper lifting, sudden twisting, or traumatic events. Here's information on diagnosis and treatment: There are many potential causes of a lower back or lumbar strain: Lumbar back strain is often caused by overuse or injury to the muscles, ligaments, and tendons in the lower back. Common causes include:

Individual factors, such as genetics, overall fitness and health, and pre-existing conditions, can influence susceptibility to lumbar strain. Additionally, a combination of factors may contribute to the risk of lower back injury. Understanding and practicing good body mechanics, maintaining a healthy lifestyle and body weight, and incorporating exercises to strengthen the core muscles can help reduce the risk of lumbar strain. Also, there are just some activities that carry a high risk of back injury and lumbar strain. Whether it's at home or on the job, activities that involve repetitive bending, lifting, and twisting, particularly with heavy weights, will eventually cause a lumbar strain. So, What causes the pain?? The pain experienced after a lumbar strain is primarily attributed to the inflammation and damage to the soft tissues, including muscles, ligaments, and tendons, in the lower back. Several factors contribute to the development of pain in lumbar strain:

It's important to note that the severity of pain can vary based on the extent and location of the injury, individual pain thresholds, and the presence of any underlying conditions such as arthritis. Proper treatment and management, including rest, physical therapy, and pain medications, can aid in the recovery process and alleviate discomfort. A common component of any lumbar strain is the muscle spasm that follows the muscle injury - that can be intense and disabling, and can last alot longer than you'd expect. None the less, that aspect will get better over time. If pain persists or worsens, there may be a more extensive injury or damage to other tissues, and it's time to seek additional medical advice for further evaluation and intervention. Diagnosis:

Treatment: Lumbar spine strains can typically be managed through conservative, non-surgical treatments. These treatments focus on reducing pain, inflammation, and promoting the natural healing of the injured tissues. Return to full activity, work, and recreation is the norm, but takes time and usually requires a course of active physical rehabilitation and exercise. Common non-surgical approaches include:

Surgery is rarely required for lumbar strains, and surgical treatment is generally considered only when conservative treatments fail, and the patient demonstrates evidence of a more severe associated or underlying injury such as a fracture or severe disc injury. These conditions may cause severe pain, neurological symptoms (such as persistent numbness or weakness), or show evidence of a structural instability that requires surgical correction. Surgical options may include procedures such as discectomy (removal of part of a herniated disc), spinal fusion, or decompression surgery. However, surgery comes with its own risks and recovery periods, and it is usually considered a last resort when conservative measures are not effective. It's important for individuals experiencing lumbar strain to consult with a healthcare professional for a thorough evaluation and to determine the most appropriate course of treatment based on their specific condition. In the majority of cases, non-surgical approaches prove effective in relieving pain and promoting recovery. Healthcare Professionals: There are several kinds of healthcare professionals who can provide appropriate care and guidance after a lumbar soft-tissue injury. The choice of healthcare provider may depend on the severity of your symptoms and the specialists available in your area, but should also take into account your own personal feelings about which kind of care you want to start with. Here are some professionals you may consider consulting:

It's crucial to communicate openly with your healthcare provider, providing details about your symptoms, medical history, and any relevant activities or events leading to the lumbar strain. Based on the evaluation, the healthcare provider will guide you through an appropriate treatment plan, which may include a combination of therapies or referrals to specialists. Conclusion: It can take quite a while for a lumbar strain or sprain to completely heal, and the pain can be intense and disabling. Because these injuries primarily involve muscles and soft tissues that can heal and repair, you have a great chance of getting back to normal, with enough time. Getting back to activity and health is always the goal, but it can take some time and alot of effort to get there. Because these injuries often occur at work or as the result of an accident, there is often a secondary issue of who's at fault, and who will pay, and that intensifies everything about the healing process. So, be patient, remember that your health care providers are on your side, and don't get depressed when it takes longer than you expected to get back to your old self!

Cervical Strain or Sprain: Understanding and Managing a Common Injury I want to provide you with the general information you need to get good care for these 10 common spine problems, the ones that patients most often inquire about. Specific medical advice should be sought directly from a healthcare professional. Here are ten common spine problems that my patients ask about, and I will be addressing each one individually

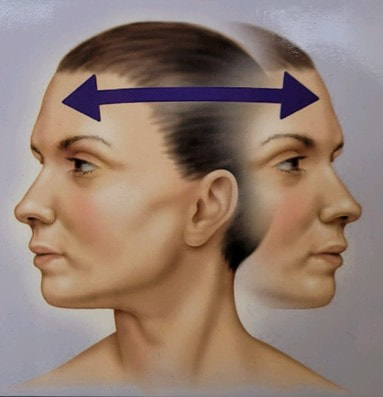

If you have specific concerns about your spine health, it's recommended to consult with a healthcare professional for a thorough evaluation and personalized advice. Let's start with one of the most common... Cervical Strain or Sprain: Understanding and Managing a Common Injury Cervical strain or sprain refers to an injury affecting the muscles, tendons, or ligaments in the neck, often caused by sudden movements or trauma. This paper provides an overview of the symptoms, treatment options, and healthcare professionals involved in managing cervical strain or sprain. Introduction: Cervical strain is a common condition that can result from various activities, including whiplash injuries, improper lifting, or sudden movements. The five most common causes that my patients run into are:

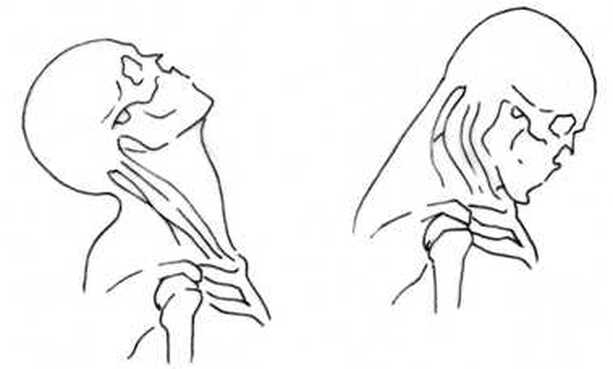

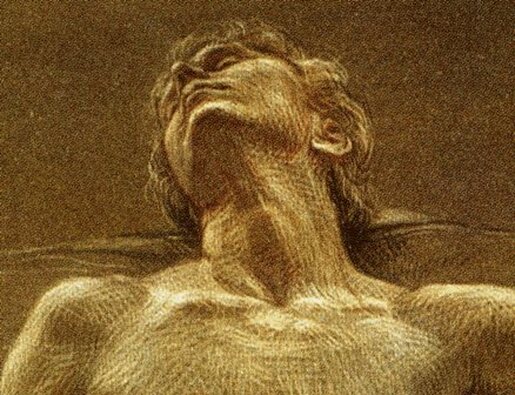

While most cases can be effectively managed with conservative (nonsurgical) treatments, severe cases may require surgical intervention. Symptoms: Symptoms of cervical strain include intense neck pain, muscle spasms, limited range of motion, headaches, tenderness, and swelling. In severe cases, individuals may experience arm pain or numbness, indicating potential nerve compression or a herniated disc. Treatment: Conservative Measures: Treated well with non-operative methods symptoms may resolve over a period of a few weeks or 2 -3 months. However, it is not uncommon for some symptoms, such as stiffness and headache, to linger for a year or more before completely resolving.

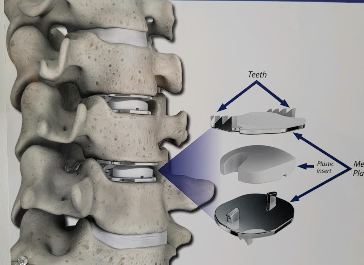

Surgical Intervention: Surgery is considered when conservative measures fail or when there is an underlying structural issue, such as:

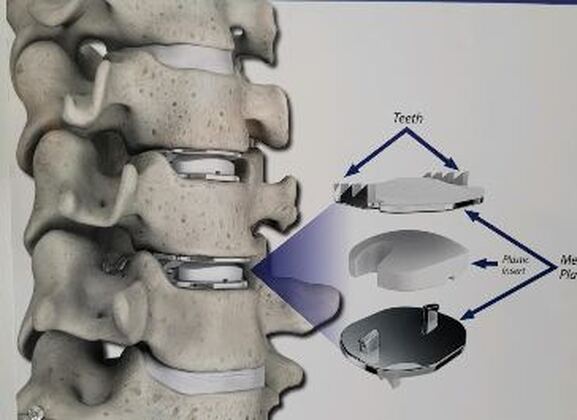

Common surgical procedures include discectomy, cervical fusion, foraminotomy, and artificial disc replacement. Approximately one patient in 10 or 20 will need surgery for an acute strain, and some additional patients may later require surgery to address late disc degeneration of instability caused by the initial strain. Healthcare Professionals: There are several healthcare professionals that may be consulted during the evaluation and treatment process:

Conclusion: Cervical strain or sprain is a common yet manageable condition. The pain and stiffness associated with this muscle injury can be remarkably intense and limiting, early on. If arm pain or weakness is part of it, the situation needs to be carefully assessed and imaging obtained by a specialist. Conservative measures are often effective, but surgical intervention may be necessary in severe cases. Collaboration among healthcare professionals is crucial for accurate diagnosis and tailored treatment plans, ensuring optimal recovery for individuals with neck and back injuries. I hope you find this helpful. In the coming weeks I'm going to address each of the common problems I listed above. If there's something you think I need to address that you don't see, just let me know!!Slips and falls are among the most common causes of back and neck sprain and injury that I see each year. Falls of one type or another injure about a quarter-million seniors every year.Falls in the bathroom can cause serious back and neck injuries, and result in fractures, severe sprains, and even death. We all know we need to be careful getting in and out of the tub, to be careful in the shower, yet I get a call about once every month from a patient that needs to be seen because they fell in the shower. If we all know better, why are falls in the bath or shower so common? |

Details

AuthorI'm Dr. Rob McLain. I've been taking care of back and neck pain patients for more than 30 years. I'm a spine surgeon. But one of my most important jobs is... Archives

January 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed