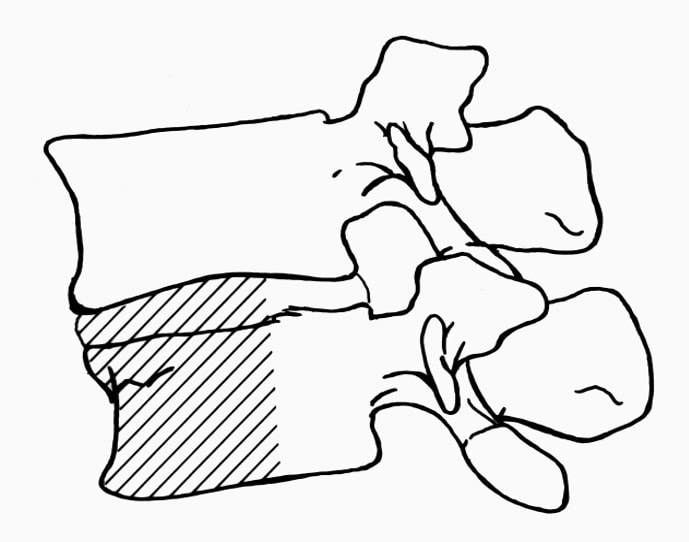

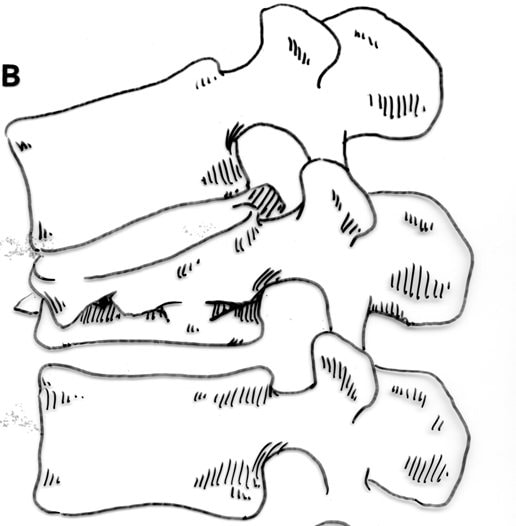

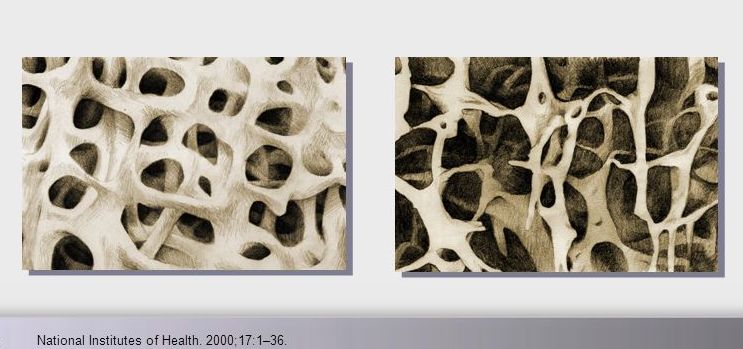

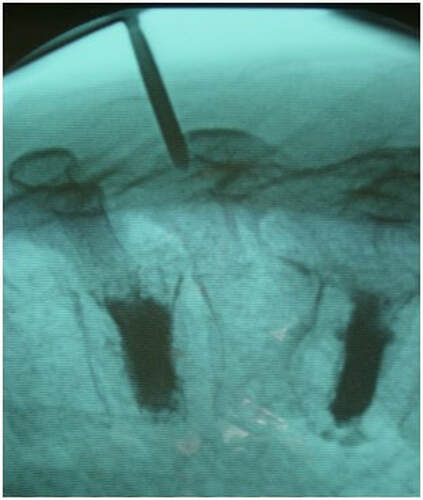

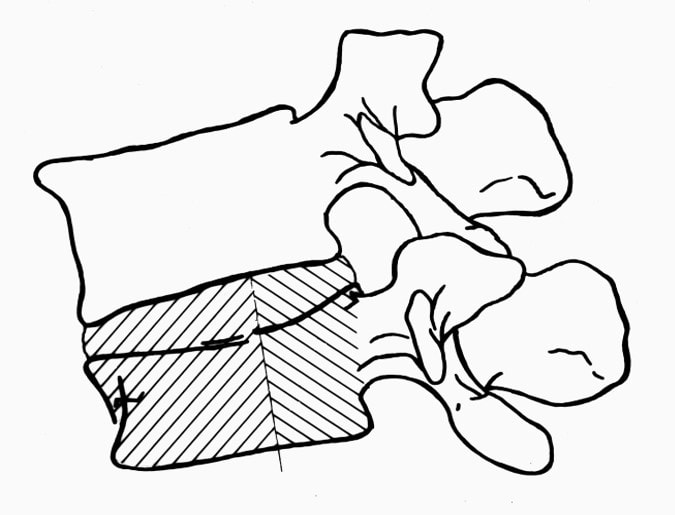

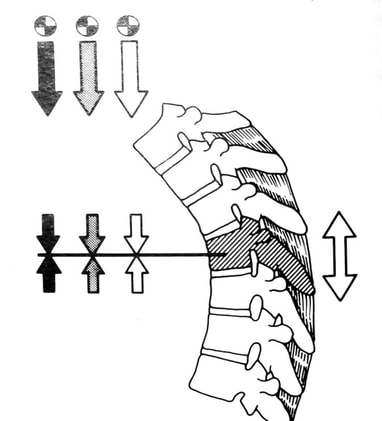

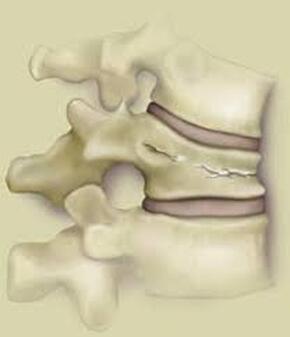

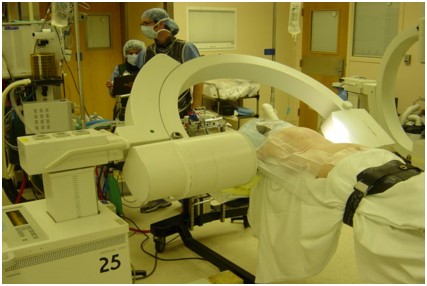

Osteoporotic compression fractures are the most common spinal fractures we see, and have gotten more common as we live longer and experience more problems with bone strength and health. If left untreated, vertebral body compression fractures can lead to progressive kyphosis, cord compromise, and intractable pain.At the same time, we have developed better ways to treat bone disease and these fractures, allowing minimally invasive treatments that can prevent progressive deformity and speed healing and symptomatic relief. So there’s rarely a good reason to treat these spinal fractures with what was once called "benign neglect". There are approximately 700,000 vertebral body compression fractures in the United States each year resulting in around 70,000 hospitalizations. The most common fractures that affect our aging population occur in osteoporotic bone – bone that has lost some of its structural support and strength and some of its calcium mineralization. Patients with osteoporosis, and those with metabolic bone disease (loss of bone mineral content due to metabolic disease) are at increased risk for a number of different fractures, but vertebral fractures are among the most common and, potentially, most disabling. 1. What is a pathological fracture? Fractures happen through any bone when the forces exerted on it are high enough to exceed its strength. This happens in automobile accidents, falls down the stairs, or poor decision-making on skis, skateboards, or bicycles, when normal healthy bone isn’t able to stand up to extreme loads. These injuries often require surgical treatment because in these high-energy injuries the bone may be fragmented and the surrounding tissues traumatized. These injuries are easily recognized, in most cases, and the need for treatment easily understood. Pathological fractures occur when the bone is not normal – it has lost much of its strength due to bone loss or mineral (calcium) loss or both – and it is liable to fail and fracture at much lower loads and forces, loads the normal body handles easily. Osteoporosis is the leading cause of the bone weakness that leads to these low-energy injuries, and it affects many older patients throughout the country, most of whom have no symptoms of pain or of impending danger until they experience a minor fall and break something. Then it’s too late to take simple measures. 2. What is Osteoporosis? Osteoporosis is primarily a physical loss of bone structure – the struts and connecting pieces that make up bones internal structure get reabsorbed and removed from the marrow (trabecular) bone, progressively weakening the overall framework. The bone that’s left behind is normal bone, mineral-wise, but there’s just not as much of it as there was when you were younger. Why would the body remove these important skeletal structures? Because the body is efficient and doesn't like carrying around stuff it isn't using! If the patient has become less active, then the body has metabolic systems that will decide that not as much bone is needed to meet the daily physical demands. The body is very frugal in some ways and will begin to remove the bone and mineral it thinks is excess from areas of lower load and either use it elsewhere or discard it. This can happen at any age, and we do see this process in younger adults who spend time in a cast or in bed and can’t be as active as normal. The difference is that young people catch back up quickly when they get back to activity. In an older patient, who may have stopped exercising because of an arthritic hip, for instance, and then spent time in bed after another injury or illness, bone loss can be rapid and hard to recover from. Illness, hormonal changes, or medication use can also affect bone strength, driving the loss of bone or depleting calcium and minerals away from the bone irrespective of activity or diet. When all of this is combined with the loss of important hormones that naturally follows menopause in women, bone loss can be severe and pathological, or “fragility” fractures become common. This is why bone health needs to be part of every woman’s routine medical follow-up and bone density (DEXA) scans should be periodically used to check for osteoporosis before it becomes severe. That doesn’t mean men are off the hook! Just that the problems are less common and tend to move more slowly in men as they age. And, there are other causes of osteoporosis and fragility that can affect anyone, regardless of gender age or activity. There are certain types of cancer that may severely weaken bone before they can be successfully treated with radiation or chemotherapy. Many patients with inflammatory disease or different types of arthritis may require steroid medication that can cause severe osteoporosis. And other medications and illnesses can do the same. Some of these patients will experience vertebral compression fractures despite careful surveillance. 3. What is a Compression Fracture? Compression fractures are the most common and least dangerous vertebral fracture that we commonly encounter. They are specifically defined as a fracture of the vertebral body that disrupts the anterior wall of the vertebral body, without disrupting the posterior cortex or pushing bone into the spinal canal. The posterior elements are always uninjured, so the spine remains stable, and neurological injuries are very uncommon. These fractures occur after an “axial-loading injury” – an injury where the forces applied to the vertebral body are directed straight down the spine and compress the vertebral endplates, the way a person might step on a pop can to try and crush it. And the injury causes the bone to crush down much like that pop can – the top and bottom are left intact but the side walls collapse down, sometimes a little, sometimes alot! The vertebra shortens and tends to collapse into a wedge. The higher the force applied, and the weaker the bone, the greater the degree of collapse and the weaker the bone, the easier it is to collapse the side walls in the first place. Most healthy people that have a compression fracture will get over the fracture pain pretty quickly, and the degree of collapse, if not severe to start with, will tend to stay stable and not progress. The fracture will heal, pain will lessen and resolve, and the only long-term finding will be seen on future x-rays, where the comment may be “Looks like you had an old compression fracture”. At that point the patient may recall something like “Well I did fall off the roof when I was younger…I was REAL sore for about a month, but I got better”. However… When osteoporosis is involved, that fracture force doesn’t have to be so great – “I just slipped off the stool I was sitting on!” – and the fracture is more likely to keep collapsing before it finally heals, which means the pain can persist for months. Worse, the final healed spine can end up badly collapsed. And that collapsed, wedged vertebra puts its neighboring vertebrae under increased stress which greatly increases the risk of another level experiencing the same fracture and collapse with the next minor fall. This progressive, serial spinal collapse is responsible for the common hunched deformity seen in many elderly women, so uncharitably referred to as the “Dowager’s hump”. Not my terminology. That progressive serial collapse has serious implications beyond just being painful. The collapsed spine can collapse the chest cavity, compress the stomach region, interfere with breathing and eating, and seriously impact health and fitness! And the persistent pain associated with these multilevel fractures and the spinal deformity may not go away once these fractures heal in such a bad position. So we want to prevent that first fracture, and prevent it from collapsing down when it does occur. And that’s where minimally invasive surgeries such as Vertebroplasty and Kyphoplasty come in. 4. Can Surgery Help? Big open surgeries are rarely necessary or reasonable in treating osteoporotic compression fractures, but two minimally invasive surgical techniques - Vertebroplasty and Kyphoplasty - have proven beneficial and easily tolerated by patients with persistent fracture pain and progressive collapse. Both of these procedures are performed through a thin cannula (think fat needle) that can be guided into the fractured vertebral body under fluoroscopy. Once inside the fractured bone a doctor performing the vertebroplasty will inject the fracture region with a fluid form of polymethylmethacrylate – bone cement – to fill in the spaces between the pieces of broken bone and stop the collapse of the fracture. The doctor will watch that cement flow carefully under fluoroscopic guidance and stop injecting as soon as the fracture region is filled in or there is any sign of leakage outside of the bone. In just a few minutes, before the patient is even off of the operating table, the cement has hardened and become rock-solid. Once the cement hardens the fracture stops collapsing, and bone healing will go ahead and permanently repair the fracture. And once the bone fragments stop moving, back pain gets better quickly and the patient can get up and around and start getting healthier. Kyphoplasty is somewhat more complex, but the principles are the same. Through that same cannula system, a core of bone is removed or a pilot hole is made into the heart of the fractured vertebra. Once that small hole is created, a specially designed “balloon” is advanced down into the bone cavity into just the right position. Now, as the balloon is carefully inflated with a saline solution, the collapsed vertebra can be restored to a more normal height and the fracture corrected. Because kyphoplasty allows the surgeon to create an open space where the fractured bone was, the cement is injected in a much thicker state, reducing the risk that it will leak out around the nerves or flow into the spinal canal. Again, at the end of the procedure the bone cement hardens and the patient awakens ready to get up and start back to activity without further restrictions. The improvement is often remarkable – patients who were unable to get up and down from bed because of fracture pain can, after kyphoplasty, literally get up and make their bed. 5. What’s the downside to such a straightforward procedure? Fortunately, major complications are very uncommon, but since these procedures are often needed by elderly or frail patients, we take the risks of anesthesia and medication seriously. Many patients will be kept overnight to insure there are no adverse reactions to the anesthesia. The most common complication of these vertebral augmentation procedures has been radicular (nerve) pain caused by migration of cement into the space around the spinal nerves. In most patients, small intradiscal and paravertebral leaks of cement have no clinical importance, but there have been case reports of severe neurologic complications, underscoring the need for appropriate technique and safeguards provided by skilled practitioners. Permanent paralysis has been reported, but is exceptionally uncommon if the procedure is performed in a controlled, image-guided fashion (by using a bi-plane real time fluoroscopy unit). The anticipated complication rate is higher when treating tumors (10%) than for osteoporotic compression fractures. So then, Who needs Kyphoplasty? Most compression fractures that occur in normal bone heal rapidly, without trouble. And fractures in osteoporotic bone usually do as well...but they need to be watched. If you have a compression fracture, diagnosed by x-ray after a fall, and you have osteoporosis or other risk factors, you should see your primary doctor back for a follow-up x-ray at 4 - 6 weeks to make sure the fracture isn't continuing to collapse. If it is, then vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty may be needed to avoid progressive deformity and pain. And, if you've had a fracture, and even though it doesn't seem to be progressing the pain just isn't going away either, this may represent another form of failed healing - a nonunion - that can be effectively treated with kyphoplasty.

In either case, it makes sense to see your spine surgeon for a consultation to make sure nothing has been missed. If you happen to be the one with the fracture, and you need to see a specialist, I'm glad to see you if we're in your area. If that's the case, call 800 670-0302 to arrange an appointment! I hope you found this discussion useful and interesting. Please let me know if there are other topics you'd be interested in learning about, and check out my Facebook page for updates on future topics.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

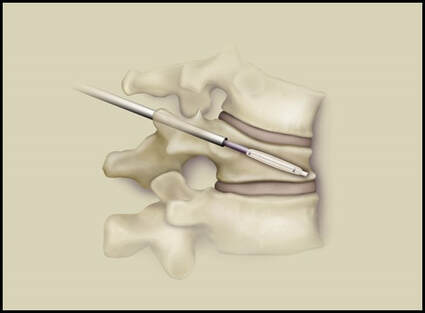

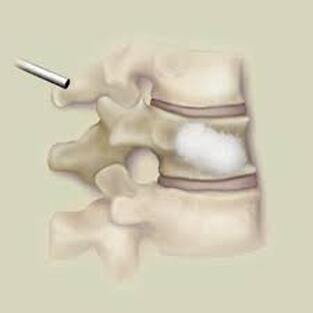

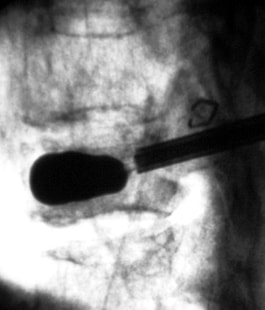

Details

AuthorI'm Dr. Rob McLain. I've been taking care of back and neck pain patients for more than 30 years. I'm a spine surgeon. But one of my most important jobs is... Archives

January 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed