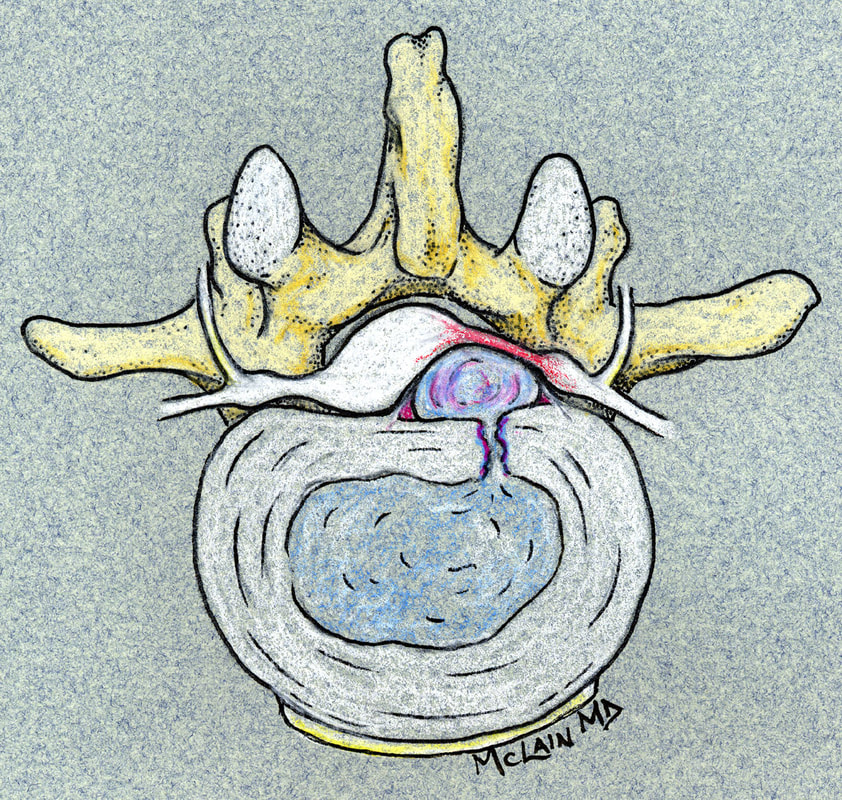

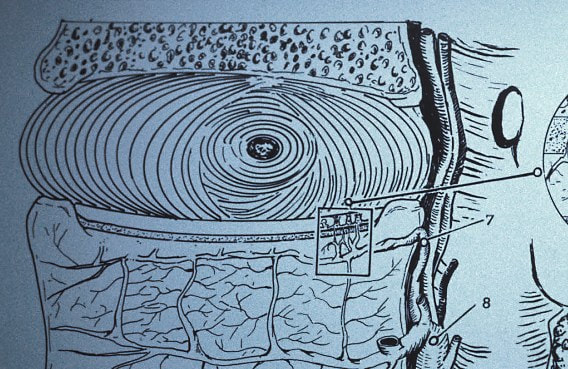

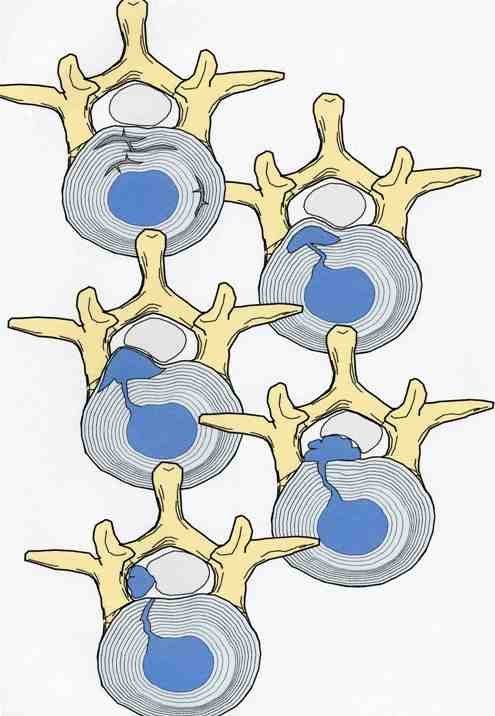

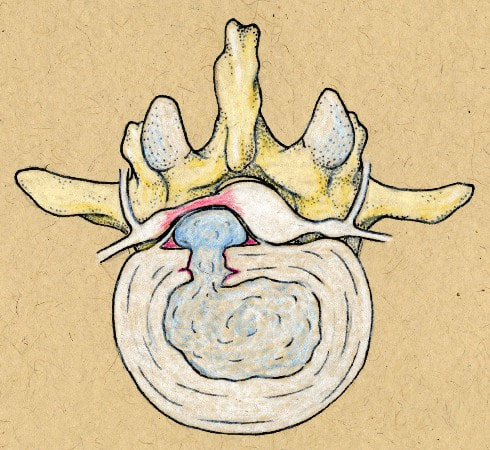

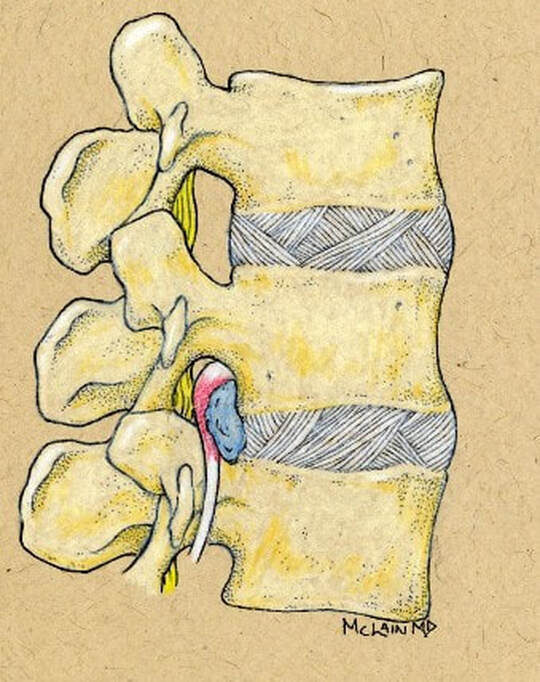

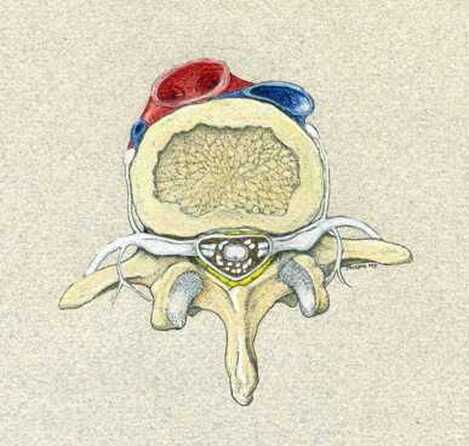

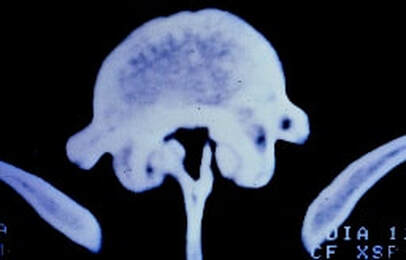

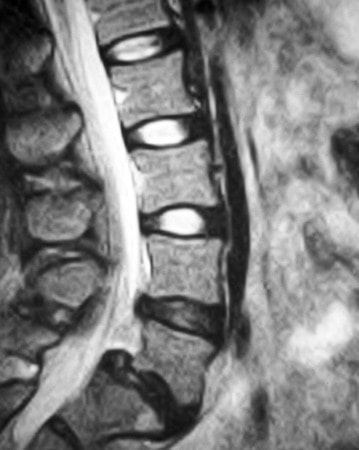

Herniation of the lumbar intervertebral disc is one of the most common, and most painful, problems that normal, healthy adults can encounter. Microdiscectomy is one solution.A disc herniation can develop slowly over time or appear out of the blue, with no warning. It can happen when you might expect it, while lifting too much or working at a heavy job, or when you'd least expect it - while sitting at your desk or turning to answer the phone. Most will get better with non-operative therapy but, when they don't, surgery is often necessary. The good news? In the case of lumbar disc surgery, the operation is minimally invasive, very reliable, and quite effective! What is a disc herniation? A disc herniation, or Herniated Nucleus Pulposus (HNP) is an injury to the disc that separates two adjacent (usually lumbar) vertebra and maintains spinal alignment and function. The disc is a tough structure made up of an outer annulus, constructed of overlapping tough fibers (like those bias belts we used to see on tire commercials) and a more spongy and softer material in the center called the nucleus pulposus. The annulus keeps the nucleus contained so it can act as the shock absorber as the spine moves and works during the day. When a disc herniates there is a displacement of the central portion of the intervertebral disc (nucleus) into or through the annulus fibrosis. A painful symptomatic HNP produces chemical and mechanical irritation of the adjacent spinal nerve, causing radicular pain - pain running down the length of that nerve into the leg or foot. There are many different grades of disc herniation, but whether they cause symptoms depends not only on the size of the herniation, but the size of the spinal canal into which it protrudes. Some small people have lots of extra room and may not be bothered much by even a large herniation. Some very big people have a surprisingly tight spinal canal and may find even a modest herniation intolerable. What kind of herniations are there? You may see, if you read a radiologists report, discs described as Protruding or Herniated or Bulging and wonder which one is worse? The first thing to know is that this terminology is descriptive, not really classified in any way, and can mean different things to different people. And, different readers use different terms for the same thing. The term "Herniation" implies displacement of nucleus material, not just bulge of the annulus, but some radiologists and doctors will call any noticeable bulge a "small herniation". Why make this point? Because I often meet patients who've been assured that they "have four herniations" in their back, when only one is truly herniated and the rest are pretty much normal for anyone over 40! The Normal nucleus pulposus sits centrally in the disc, 2/3 back from anterior rim of the annulus. The normal annulus fibrosis contains the nucleus, and does have a slight convex bulge when it's healthy. There is no impingement of the annulus on the adjacent neural structures - the nerve roots or the spinal cord/cauda equina. A disc Protrusion implies that the nucleus protrudes through inner annulus and pushes the outer annular rim out into canal or foramen, impinging on the nerve roots and causing pain. A protrusion may be broad-based or focal. An Extrusion implies that the nuclear material has pushed through the outer annulus and herniated into canal where it can now directly press on the nerves or irritate them due to inflammation. An extrusion can be sub-ligamentous, contained within the last layer of the annular structure, or free, meaning completely out into the canal. And, direct contact of this nuclear material with nerve root is irritating. A less common presentation is a Sequestered Herniation. In a sequestered disc, the nuclear fragment has pushed through into canal, become separated from annular defect and remaining extruded disc, and may migrate some distance away from its original position. MRI's show us this well, but if the MRI is old, the migration could happen later and leave you with a disc fragment that isn't visible during surgical decompression. There's a reason we want a "recent" MRI! Why does a herniated disc cause so much pain in the leg and foot? Direct pressure on the adjacent nerve root results in numbness and weakness in the radicular distribution of the nerve, the region that that particular nerve gets sensation from and sends muscle messages to. Direct pressure can cause rapid loss of sensation, severe pain and weakness, but even light pressure can be a problem. With time, inflammation starts up around the herniation and the compressed nerve, and with inflammation, even minor irritation of nerve generates intense pain in the radicular distribution. And, if the herniation is in just the right (or just the wrong!) spot, pressure over a specific nerve center called the Dorsal Root Ganglion generates immediate and intense pain. Depending on which nerve is involved, a patient with a symptomatic disc herniation loses sensation over specific area that that nerve serves (dermatome), loses strength in the specific muscles that nerve innervates, and may lose reflexes in specific joints those muscles control. The Classic presentation of an acute HNP, often follows this pattern:

That new pain is Sciatica - radicular pain traveling down one of the nerves that make up the sciatic nerve - L4, L5, or S1 - which are the most commonly affect because most disc herniations occur at L4-5 and L5-S1 levels. Because the anatomy of the nervous system is very consistent, and we can ask the patient exactly where their leg pain is most intense, clinical diagnosis of disc herniation and the level is usually precise and reliably. In those cases surgical treatment is also, usually, precise and reliable. Will disc surgery make my back pain go away? That's harder to predict. While most patients do get improvement in their low back pain, the actual cause of anyone's back ache is usually uncertain due to the many potentially pain sensitive structures in lumbar spine. So, if the disc herniation was THE cause of the back pain, the prognosis is good. If muscular deconditioning, degenerated discs at other levels, or arthritis of the small facet joints was the primary reason your back hurt, discectomy may not solve everything. Will disc surgery make my leg pain go away? This is far more reliable. If pain is caused by direct pressure on the nerve or even direct contact with the nerve, removing that disc fragment relieves the leg pain symptoms in the vast majority of cases, and sometimes immediately. How reliable is this? It depends on how reliable our diagnosis and surgical plan were: In years before MRI or myelogram were available, surgery was based on just one thing - the doctor's clinical examination of your neurological system. Based on just this, a discectomy was more of an exploration, but was still successful in about 55% of cases. Over time, doctors became more aware of what was causing the pain and developed better examination techniques, one of which was called the Straight Leg Test. This test slightly stretches the nerve over the protruding disc, and intensifies the pain for a moment, confirming the diagnosis that there is a herniated disc to be treated. With the neurological exam and the straight leg test, surgical success improved to over 85%. We still do that physical exam and are still pretty sure what we need to do before we do anything else, but now MRI lets us look inside the spine anytime we need to to confirm our suspicions and characterize the size, shape, and location of the disc fragment. With the addition of a quality MRI study, surgical success is routinely better than 95%, meaning 19 out of 20 patients come back saying: "I'm much better. I'm glad I did it. Wish I'd done it sooner!" Will I get that "great" clinical result? Our best surgical results are obtained among patients with

What are the chances it's something that's more difficult to fix? There are a couple of spinal conditions that we always look for on spinal imaging during our work-up. Fortunately, the principle imaging studies we always do for a disc herniation - x-ray and MRI - will warn us when one of these problems threatens to "complicate" things: Spinal Stenosis often overlaps with HNP and the two may exist together for years. The primary findings that suggest that spinal stenosis will require a more extensive decompressive laminectomy are:

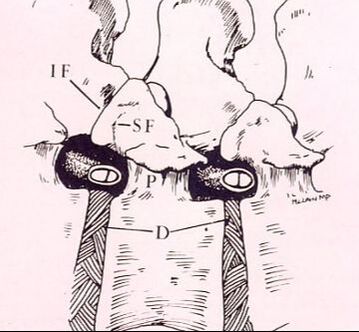

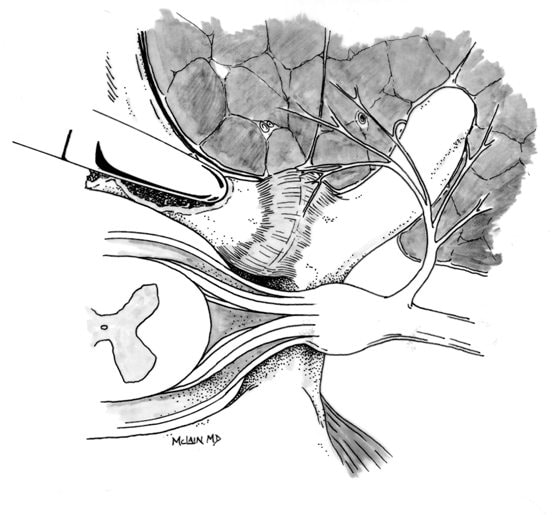

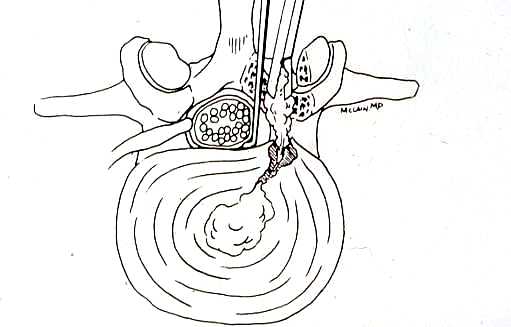

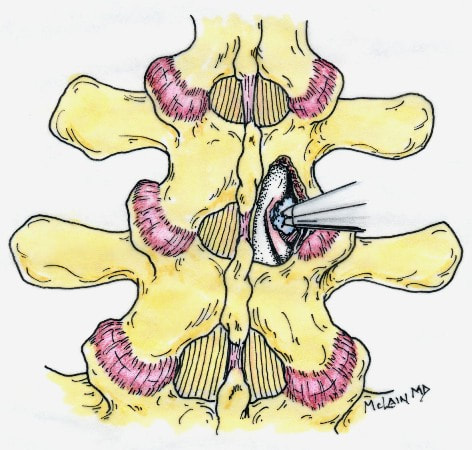

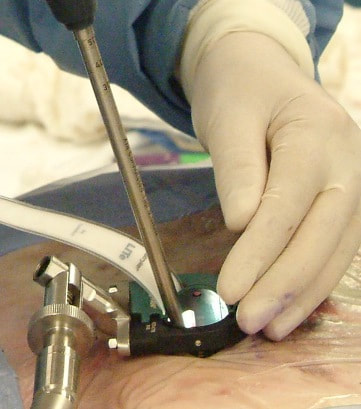

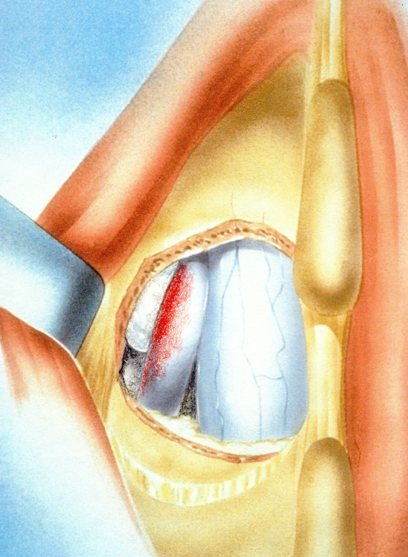

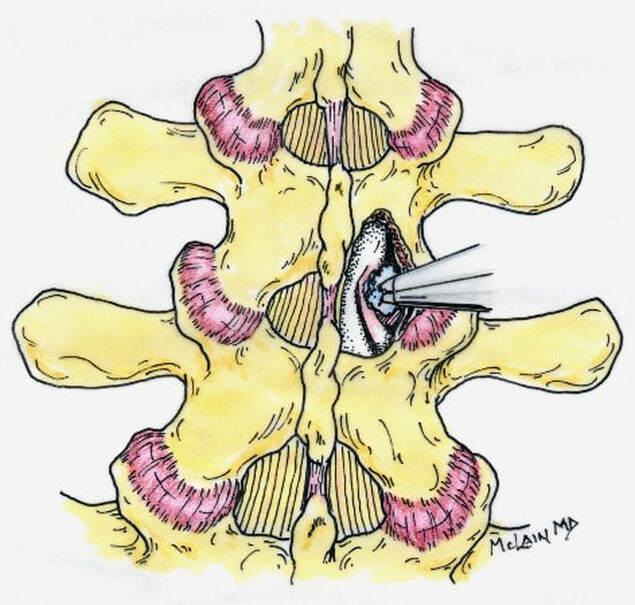

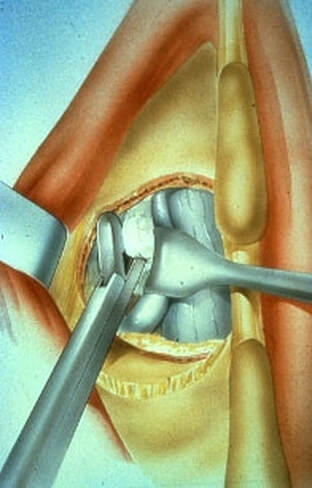

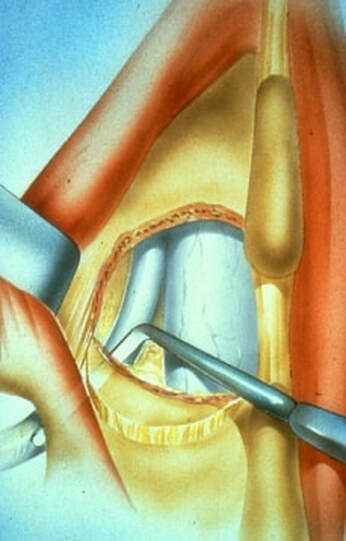

Degenerative Spondylolisthesis can cause severe stenotic symptoms along with LBP. This condition usually results in specific severe low back pain due to deformity and instability, but if the "slip" isn't unstable the back pain may be more tolerable than the leg pain and decompression may be all that's necessary. So what are the surgical options, if time, physical therapy, anti-inflammatory medications and injections haven't gotten us anywhere? The primary approach to a symptomatic HNP is through microdiscectomy. This is a minimally invasive operation, routinely performed as an outpatient procedure, that removes the offending disc fragment, decompresses the nerve and removes any bone spurs that may be contributing to pain, without disturbing the adjacent joints or soft tissues important to spine function. Carried out in most cases using an operating microscope and fluoroscopic imaging to confirm levels and alignment, microdiscectomy is highly successful with a very low incidence of serious complications. It's minimally invasive, but it's not minor surgery, however. Microdiscectomy is performed through a 1 to 2-inch incision in the middle of the back, centered over the level of the disc herniation. After incising the skin, the back muscles are separated from the bony arch (lamina) of the spine and pulled to the side. These back muscles are held to the side with a special retractor or penetrated with a tubular retractor so they are out of the way during the surgery. The surgeon then removes the dense tissue that covers the nerve roots (ligamentum flavum) and removes enough bone around the edges of the interlaminar space to create a window (more like a sky-light) called a laminotomy, allowing us to introduce specialized instruments into the spinal canal. In many cases a small portion of the adjacent facet joint is removed to relieve any bone spurs putting pressure on the nerve and make it easier to remove the herniated disc fragment. The nerve root is gently moved to the side with specially designed instruments, allowing the surgeon to get under the nerve root and remove the extruded fragments of disc material that are compressing the nerve. Depending on the situation, specially designed instruments are passed into the disc itself to remove any loose fragments of disc that might herniate later. Any healthy, well attached disc material is left in place. After the nerve is decompressed, a careful search is made to insure that no fragments are left behind. The laminotomy is covered with a material to limit scarring, sometimes along with an antibiotic, and the procedure is over. The retractors are removed and the muscles fall back into place. The patient is usually up at bedside within half an hour, and able to go home an hour or two after that. Nerve pain usually improves quickly - sometimes right away - but may take a few days to weeks to get back to its best level. There are potential risks with any operation, and your surgeon will discuss those individually when you talk about surgery, but major complications are rare in the hands of an experienced surgeon. So, How do you know when you Need Surgery?

When pain is intolerable, unresponsive to the non-operative therapies that so often help others, and is clearly related to a large disc herniation, then continuing to put off surgery can lead to nerve damage or scarring that make later treatment less reliable and more difficult. It is appropriate to give non-operative care a real chance though, as most patients will see improvement in the first few weeks after an acute herniation and may never need an operation. If symptoms persist, however, or nerve root or spinal cord compression is severe enough to cause weakness or disturb bowel or bladder function, surgery may be the most reliable and rapid solution to the problem. Whether it's a simple disc herniation treatable through microdiscectomy and laminotomy, or it's a more complex problem involving spinal stenosis or a spondylolisthesis, you will want to talk to a spine specialist about the option that suits your situation best. Which is where I usually come in. So, if you are having problems similar to this or any condition that you've been told will require surgery, and we are in your area, please feel free to contact my office for a consultation! I hope you found this article interesting and informative. Follow me on Facebook to get updates on new content, and feel free to comment if you like this post or have other questions you'd like me to address. Thanks Again!

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Details

AuthorI'm Dr. Rob McLain. I've been taking care of back and neck pain patients for more than 30 years. I'm a spine surgeon. But one of my most important jobs is... Archives

January 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed