Back pain of one type or another affects 9 out of 10 adults at some point in their lives, and at any one time about 30% of the people around you would admitting that they are suffering from low back pain right then.It is one of the most common complaints of patients presenting to emergency rooms, doctors offices, and urgent care centers, which means it often gets the kind of attention we give the "common cold". Because the causes of pain typically relate to minor trauma or benign, age-related degenerative changes, and because 90% of patients will improve with simple supportive care and physical therapy, patients rarely see a specialist - and may not see a doctor - before being sent home with mild medications and advice to follow-up with their regular doc if the pain persists. While the vast majority of back pain episodes do respond to time and a little supportive care, there are some serious, uncommon causes of back pain that physicians can't afford to overlook, yet may not recognize right away. Doctors like the saying "Common things happen commonly" to remind younger Docs to focus on the most likely cause of a patient's problems first. Serious but uncommon medical disorders account for less than 1% of all causes of back pain seen in a primary care practice, and the time and effort invested in looking for these uncommon disorders is considerable. So, if a patient's symptoms are typical and their presentation is common, then there is little reason to put the patient through the time and expense of searching for something that's not likely to be there. That doesn't mean we should forget about those more ominous conditions: When the symptoms are unusual, or the story isn't quite ordinary that your doctor may want to look for more serious underlying problems. When symptoms don't fit the usual pattern for a back strain or disc herniation, or when the symptoms persist too long to be explained by the usual conditions that affect the spine, that when we consider the diagnosis of Atypical Back Pain. Patients with Atypical Back Pain warrant a more careful evaluation: a more detailed history and a more extensive physical examination, looking for specific signs and symptoms, may turn up a clue that something more serious is lurking in the background. And more focused and specific diagnostic studies may look not only at the spine but at the associated systems that can mimic back pain symptoms. In most cases this careful examination can confidently "rule-out" more ominous underlying disease, and focus attention back on the proper course of rehabilitation and low back care, but in an important few, a serious underlying cause can be identified and treatment started! When do we consider back pain "Atypical"? The character of pain in patients with a more serious underlying disorder differs from common low back pain . Benign (ordinary) back pain is typically activity related, relieved by rest, and is often precipitated by a recognized injury. Typical, acute back pain begins to subside after four to six weeks. Pain caused by more serious spinal or physical disorders is atypical in that it:

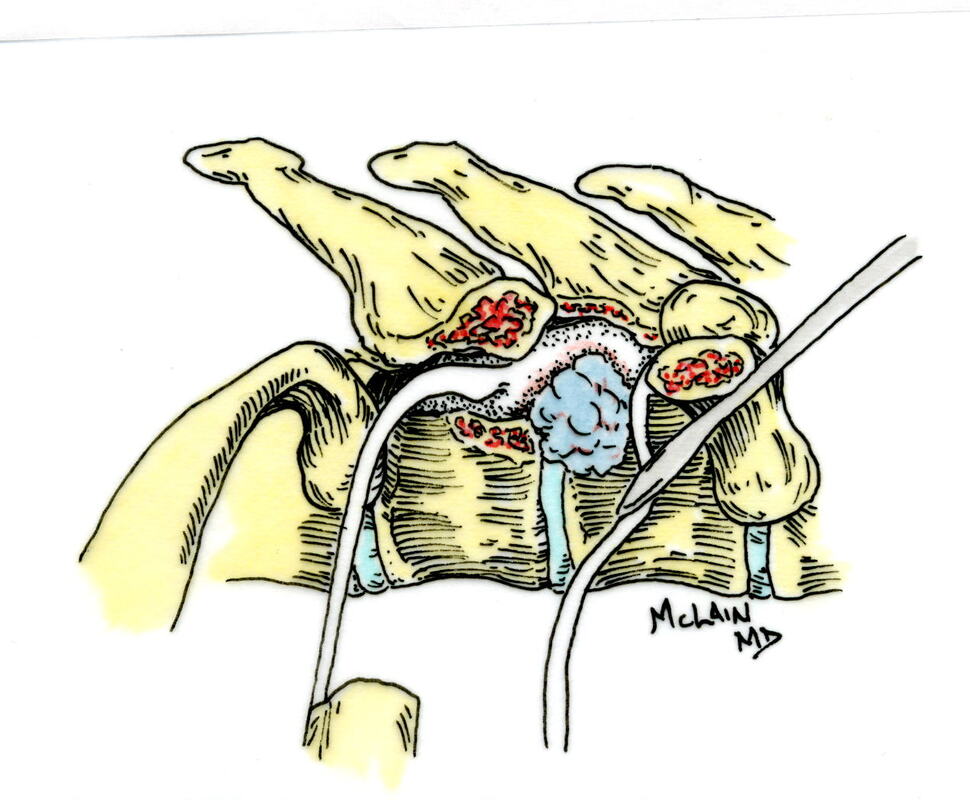

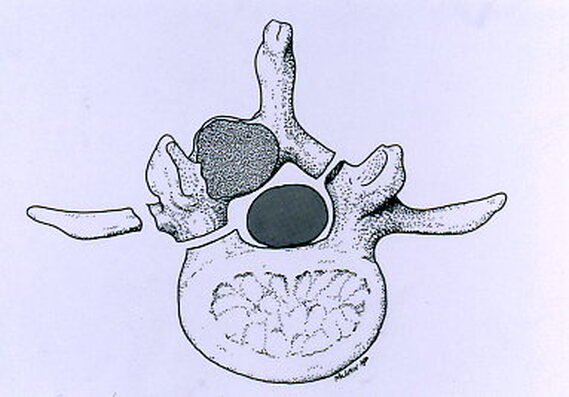

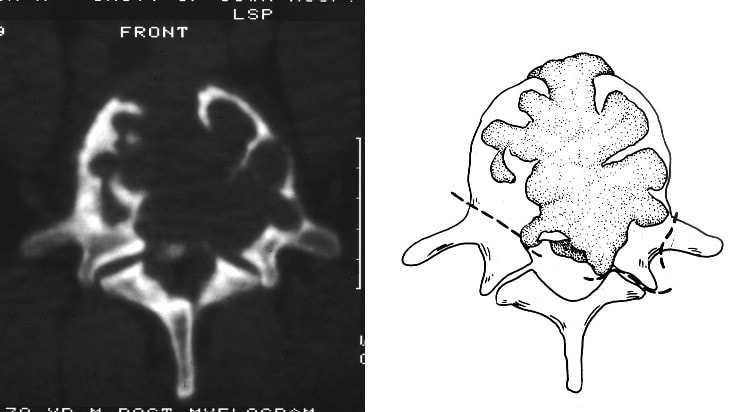

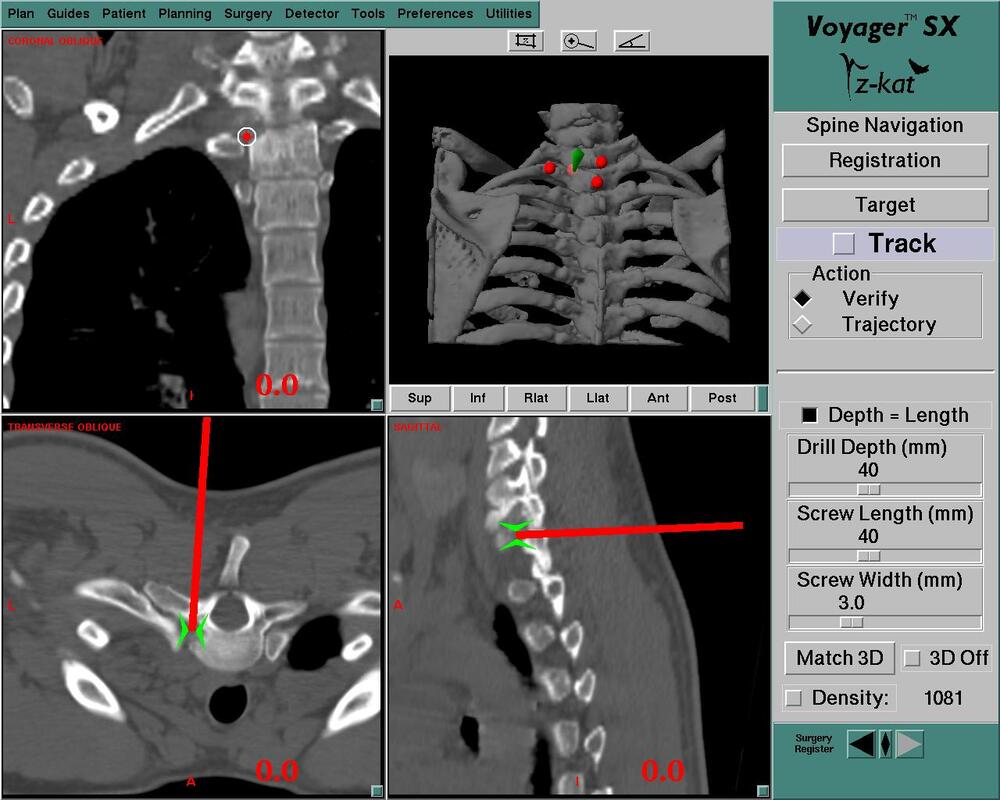

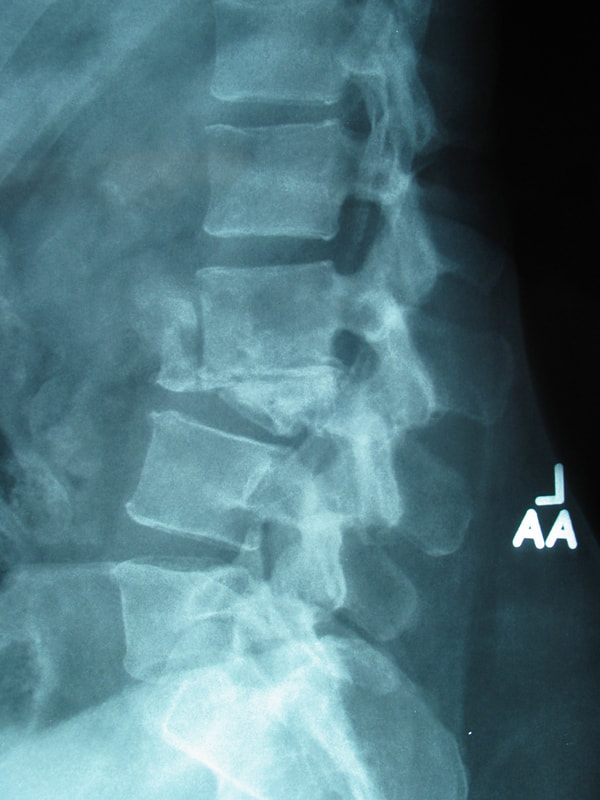

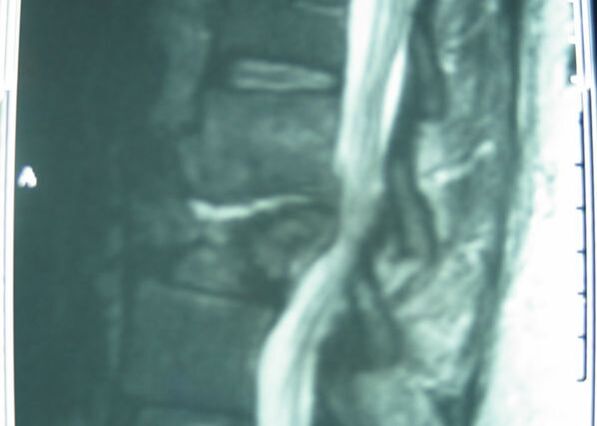

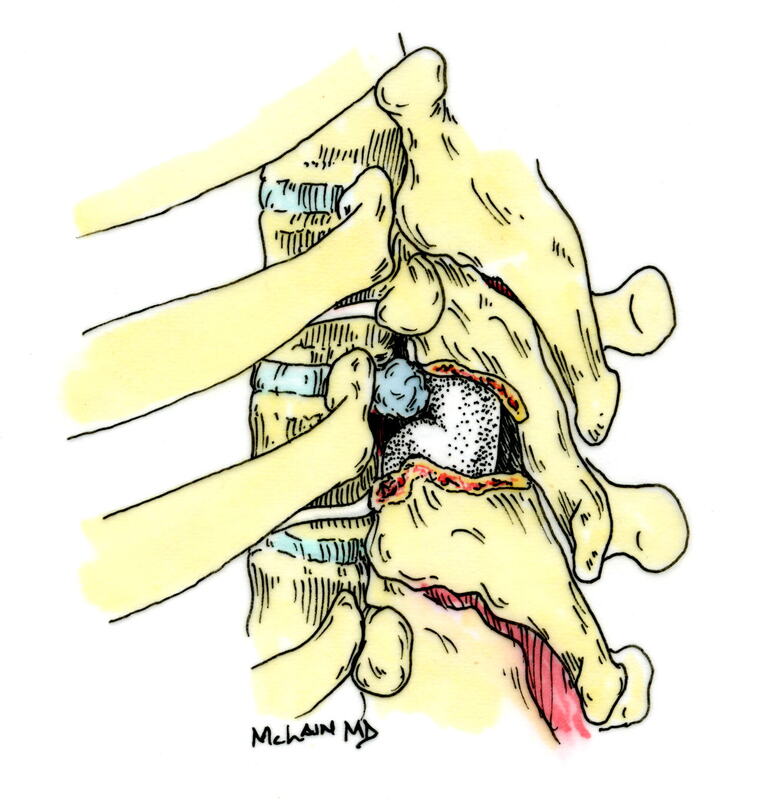

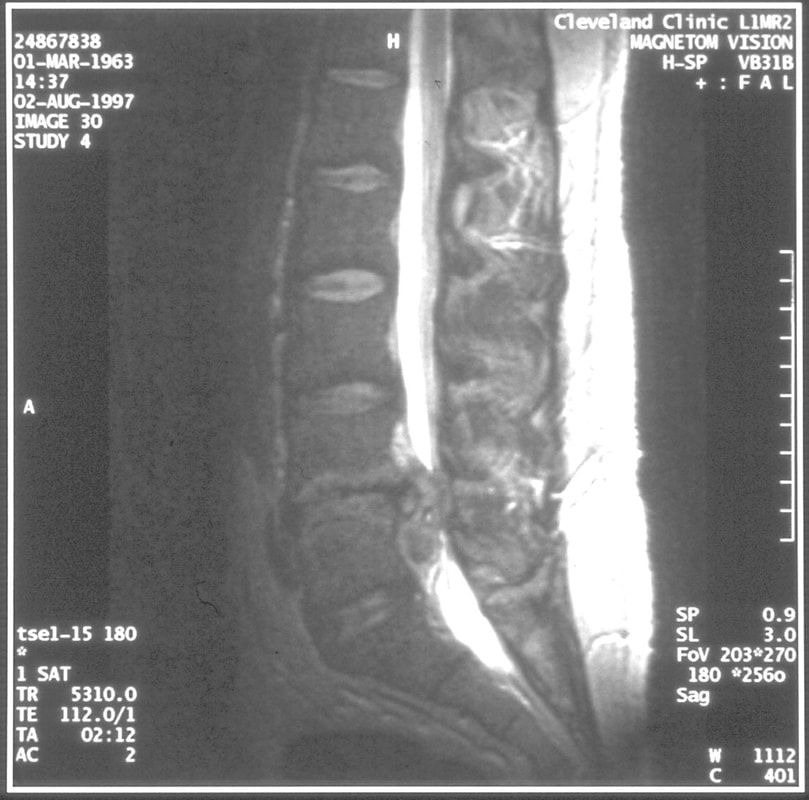

Typical muscular strains and sprains may be most tender in a region, often across the lumbosacral junction, but pain that is intense and focal to the thoracic or upper lumbar spine is less typical, and deserves a closer look. If that pain is associated with belt-like symptoms of rib or flank pain, or radicular symptoms of pain or weakness in the legs, the need for more careful assessment is clear. If you have atypical pain, what will your doctor be looking out for? Cancer in the Spine Unremitting pain often raises fears – in the patient and in the care-giver – that “something bad” is going on, and cancer is the bad thing that most people fear. Since back pain is the presenting symptom in 90% of patients with a spinal tumor, cancer is one of the first things we look for in any case of persistent, unremitting back pain. The concern is legitimate: Almost every kind of cancer can be found in the spinal column at one time or another. It is the most common site of bony metastases in the body, and it contains or is adjacent to just about every type of cell that can become a neoplasm. Tumor cells often find the highly vascular marrow of the vertebral body an easy place to grow and expand. As that happens, the surrounding bone may be distorted or expanded, or it may fracture. A growing mass of tumor tissue in the spinal canal can cause symptoms of weakness or nerve related pain by directly compressing the spinal cord or the nerve roots that serve the muscles of the body. If direct destruction of the involved bone results in weakened vertebrae, a pathological fracture may be the first sign that a tumor is present. History: Signs and symptoms of systemic cancer including fatigue, weight loss, abnormal bleeding, abdominal swelling, subcutaneous masses, or swollen lymph nodes. (AmCancerSoc). Symptoms typical of common types of cancer, such breast, lung, colorectal, kidney, or thyroid cancers, such as a palpable, mass, coughing and particularly coughing up blood, blood in the stool or urine, change in bowel habits, or unexplained weight loss should prompt a visit to your primary care doctor in and of themselves. and will guide a specific diagnostic approach when it comes to the back pain. There are risk factors that also raise our suspicions: Age greater than 50 years, previous history of cancer, duration of pain greater than 6-8 weeks, failure to improve with conservative therapy, and abnormal routine lab values including an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), or finding of anemia. If this history is concerning for the possibility of a cancer in the spinal column, the next step will be to obtain an x-ray of the symptomatic level, but also an MRI of the region (cervical, thoracic, or lumbosacral) involved. Depending on what that shows, a more specific work-up will proceed, and allow us to plan for treatment and tumor removal. Physical Examination: Carcinomas of the lungs, breasts, prostate, kidneys, colon and thyroid, along with multiple myeloma, account for 88% of all spinal tumors that we see for treatment. A careful examination of these organs and systems is carried out whenever we find a lesion in the spine that is suspected to be cancerous. We examine the spine to identify sites of focal pain, and elicit signs of spinal cord compression. Diagnostic Studies: When cancer is suspected, our initial workup will include chest x-rays, mammography, and an abdominal CT to identify the underlying primary malignancy, if one exists. Imaging of the spine itself will included the x-rays and MRI, but other studies may look for signs of metastatic disease in other bones. Basic laboratory studies may reveal anemia, hypercalcemia, and elevated levels of alkaline phosphatase. Serum and urine protein electrophoresis (SPEP and UPEP) are specific for bone marrow tumors called multiple myeloma or plasmacytoma. Urinalysis may reveal hematuria, suggestive of renal cell carcinoma. Imaging: Spinal tumors are poorly visualized on plain x-rays until the bony destruction is advanced. MRI can screen the whole spine, identifying lesions in patients with both normal x-rays and bone scans, and is the study of choice to rule-out spinal a cancerous spinal lesion (neoplasia). Special imaging studies can also localize a lesion so that modern, image guided systems can allow accurate biopsy or minimally invasive removal. If all of these studies return normal after having found a lesion of the vertebral body or surrounding soft tissues, then a needle biopsy is generally the next step in confirming the diagnosis, or to confirm that there is no cancer and that the back pain can be cared for in a more typical and less anxiety-causing way! Infection Spinal infections can come on suddenly (acute) or become apparent over the course of months (chronic). Acute infections are most often the result of a bacterial infection, while chronic infections may result from less aggressive bacteria, from rare fungal infections, or from tuberculous (granulomatous) disease. Vertebral osteomyelitis (infection of the bone) represents about 5% of all cases of osteomyelitis and is an uncommon cause of back pain. Half of patients affected are more than 50 years old and two thirds are men. The most frequent source of bacterial infections come from an underlying urinary tract infection, but any source of infection (dental abscess, infected wound, pneumonia) can spread to the spine. Immuno-compromised and diabetic patients are at particular risk. History: Patients with a spinal infection usually present with intense focal back pain, worsened by weight-bearing and activity. Patients often complain of exquisite pain relieved only when laying down. Sixty percent of patients have some sense of nerve irritation or compression (radicular pain), and nearly a third will have some signs of spinal cord compression. Fever, chills, headache, and systemic illness are present in many but not all patients. Chronic infections such as tuberculosis are often associated with weight loss and fatigue, episodic fevers, and night sweats. Physical Examination: Pain is usually well localized and reproduced by palpation or percussion over the involved level. Severe pain may be elicited simply by sitting the patient up, or by changing position. If the vertebra has collapsed, focal deformity (kyphosis) may be seen. Diagnostic Studies: The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is a sensitive test that may be the only abnormal laboratory value found, but it is increased in 92% of patients with a spinal infection. The C-Reactive Protein test will also be elevated, but almost half of patients with a spinal infection will have a normal white blood count. Remaining labs are typically normal. A TB test should be administered, with few exceptions, as many patients are at-risk individually (emigrants from areas where TB is very common, immuno-compromised patients, and patients with known exposure), and others may have no idea they have been exposed to a sick person. (Figure 2). Blood cultures are drawn in any patient with high fever, chills, or shaking chills (rigors). Imaging: The x-ray changes associated with osteomyelitis are usually not apparent for at least 4 - 8 weeks, and they may be subtle even then. An MRI is our most accurate and sensitive test as it will reveal signal changes as soon as tissue become inflamed or start developing a fluid collection. MRI is capable of differentiating degenerative and neoplastic disease from vertebral osteomyelitis. Epidural abscess occurs in 10% of spine infections, yet 50% of patients with an epidural abscess are not diagnosed until MRI imaging is completed. Patients with an epidural abscess initially complain of localized back pain, followed by radicular leg or arm pain, then weakness, and finally paralysis. With contemporary imaging capabilities and lab facilities, infection rarely comes to this point. Fractures of the Spine Fractures associated with major trauma - a motor vehicle accident or fall down the stairs - are usually recognized right away, and present little mystery. Even if the patient's pain doesn't immediately signal the presence of a broken bone, the history of recent trauma will trigger a more careful evaluation and x-ray or CT imaging will identify the problem in time for prompt treatment. Fractures associated with weakened or osteoporotic bone may be much harder to recognize. These fractures are called pathologic because they occur in weakened bone, and can be a result of osteoporosis, metabolic disorders, malignancy, or infection,. And they are common! In years past, one-third of American women over the age of 65 would suffer an osteoporotic vertebral fracture in their lifetime, making these the most commonly encountered fractures in the primary care setting. And. while fractures in normal bone are almost always associated with some traumatic event, pathologic fractures can occur after a minor slip and fall, a vigorous cough or sneeze, or just by changing position. This is less common now that we have better treatment for severe osteoporosis, but it can still happen! History: In osteoporotic patients the cause of the fracture may be minimal – a sneeze, fall from a chair, slip and fall in the home. Localized spinal pain, age over 65, female gender, European descent , and low body mass index (thin women) are highly associated with osteoporotic compression fractures. Patients receiving corticosteroid therapy for any length of time have an increased risk. Patients who have been bed- or chair-bound for any length of time will loss bone density quickly and be at increased risk when they start to get up and around again. Compression fractures are rarely associated with neurological deficits, but once you've had one, you tend to have more, because all of the bones suffer from the same degree of weakness. Plain x-rays are not as good as MRI at distinguishing a recent compression fracture from other pathologic fractures caused by infection or malignancy, and your doctor will want to investigate other areas of health if there are any other signs of generalized illness. Physical Exam: Localized pain over the involved vertebra is moderate and increased with motion and weight-bearing. Patient may complain of inability to bend or twist due to pain or muscle spasm. Diagnostic Studies: Routine labs and thyroid function tests are normally obtained. Specific laboratory studies may be ordered if there is a question of pathological fracture due to myeloma or other cancer. AP and lateral roentgenograms are the initial study of choice as they are easily obtained and compared to determine if the fracture is stable or progressively collapsing. If a fracture is diagnosed or the exam is equivocal then an MRI is appropriate to determine whether the fracture is recent or an old an previously unrecognized one. If the fracture is progressively collapsing, it's important to recognize this early as there are minimally invasive surgical treatments that can stop the collapse and relieve the pain, if the problem is recognized in time. Intra-Abdominal Diseases that can Cause Back Pain Symptoms There are a variety of disorders of the abdominal organs that can, on rare occasions, produce severe back pain, mimicking lumbar or thoracolumbar spinal disease. Though quite uncommon, some of these disorders are potentially life-threatening, and in these cases it is important that your doctor hears about symptoms that may seem to you like they wouldn't have anything to do with your spine! History: Back pain caused by abdominal (visceral) sources is usually not directly triggered by physical activity, but may come on suddenly and severely when at rest or when eating. The pain may be intense and unremitting, or may come and go, being intensely colicky, or throbbing, in nature. Pain that is:

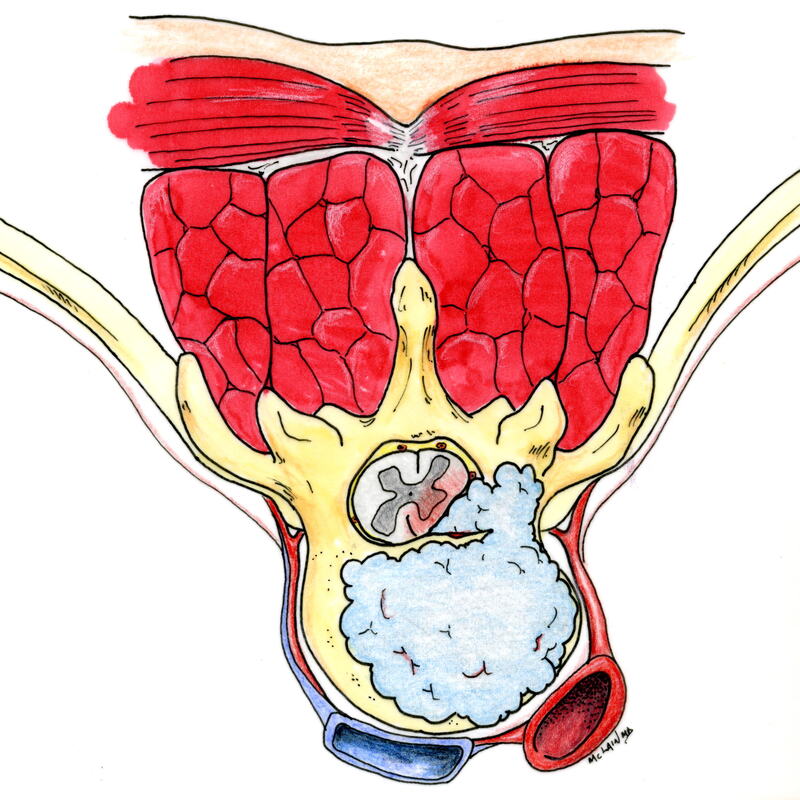

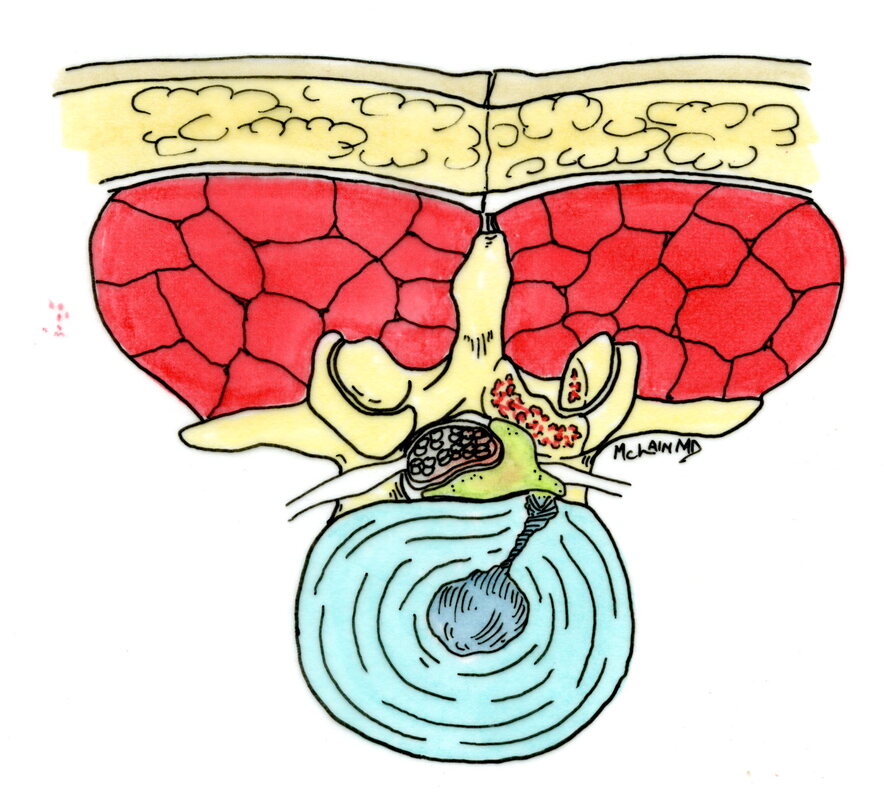

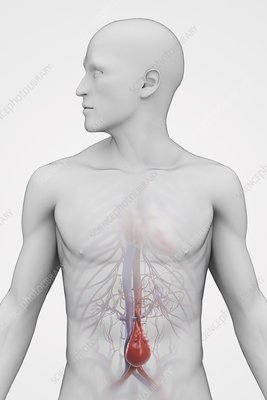

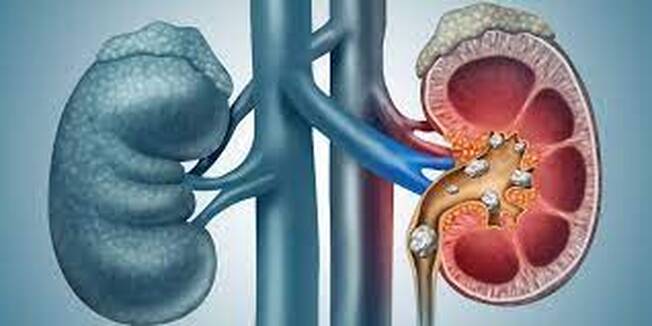

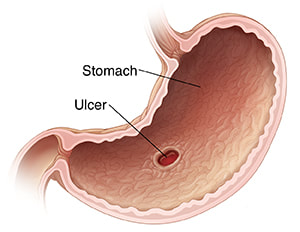

Any history of previous abdominal surgery, renal stones or gall bladder stones, gastric ulcer, or abdominal aneurysm needs to be reported to your doctor at the time of the initial evaluation. Physical Examination: Percussion over the costovertebral angle of the back will typically reproduce pain of kidney infection (pyelonephritis) or renal stone. Rectal examination will identify blood in the stool in cases of stomach ulcer or colorectal disease. Depending on the cause, the abdomen may be tender and bloated, or silent and rigid. Deep palpation by the physician may reveal guarding, rebound, or focal tenderness which are signs of an abdominal problem requiring immediate evaluation. Signs of an "acute abdomen", or palpation of a pulsatile mass in the abdomen should generate an immediate surgical evaluation. Diagnostic Studies: In addition to the routine metabolic panel, an abdominal x-ray will reveal evidence of free air, small bowel obstruction, biliary disease, or aortic aneurysm. Abdominal CT can further elucidate these findings, if indicated. Lumbar x-rays typically show the outline of the aorta as it passes along the front of the spine, and the presence and severity of an aneurysm can often be estimated from these views before the abdominal studies are ordered. Abdominal Aneurysm Thirty percent of patients with an abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) are misdiagnosed on initial presentation. An aortic aneurysm that is expanding (dissecting) can produce intense mid-thoracic or lumbar back pain, and is the most serious of vascular problems that can masquerade as a back problem. The pain of the aneurysm can be caused by compression of adjacent structures by the aorta, or by dissection of the arterial wall. The pain of aortic dissection is intense and undiminished by narcotics, and the patient appears to be in shock - sweating, apprehensive, pale and incapacitated. A pulsatile abdominal mass can be felt on exam in almost all cases. Lower extremity pulses may be diminished or asymmetrical. Patients with risk factors for peripheral vascular disease (smoking, HTN, diabetes) and those with a known aneurysm, should be assessed for an aortic dissection anytime they present with atypical back pain. Once recognized, a dissection aneurysm requires emergency treatment! Intra-abdominal (Visceral) Disorders Ulcers, especially those involving the posterior stomach wall, may cause thoracolumbar and upper lumbar back pain. A previous history of ulcers is important to know about. Renal (kidney) pain is usually experienced as colicky pain at the thoracolumbar junction and flank. Kidney infections (Pyelonephritis), renal artery occlusion, or Kidney stones (nephrolisthiasis) may all cause severe, colicky back pain. Bladder disorders may cause low back symptoms, usually concurrent with suprapubic discomfort and urinary symptoms of burning and bladder frequency. Pancreatic disease produces pain in the upper lumbar region, worse when laying down, and often associated with severe generalized illness. A past medical history of pancreatitis, jaundice, or alcoholism, with increased lab values of amylase and lipase, differentiates pancreatic pain from spinal pain. Pain of pelvic origin caused by ovarian torsion or rupture, ectopic pregnancy, endometriosis, or fibroids, may present as back pain unrelated to changes in body position or movement. New, acute onset of atypical back pain, should prompt a discussion of possible pregnancy and appropriate testing. Spinal Cord And Cauda Equina Compression Finally, there are situations where the problem is definitely coming from the spine, and the pain is definitely the result of disc disease and nerve compression, but the usual plan for the patient to rest, wait, and recover is absolutely not the right thing to do! Spinal cord compression occurs when any portion of the spinal canal above the lumbar spine is narrowed or invaded by tumor, disc, infection or bone fragments from a fracture. Cauda equina compression occurs when severe lumbar nerve compression is caused by a massive disc herniation, or by a more ominous problem such as fracture, tumor, or epidural hematoma or abscess. The finding of a cord level or cauda equina level neurological deficit should trigger your doctor to start an immediate and aggressive search for the cause. Patients with cauda equine syndrome typically present with urinary retention (can't pee) while those with spinal cord compression present with incontinence (can't not pee). The classic symptoms of low back pain, bilateral leg pain symptoms, saddle anesthesia, and lower extremity weakness progressing to paralysis, develop over hours or days, and are variably present at the time the patient presents for care. Any combination of these symptoms may exist at the time of first evaluation, requiring a high degree of suspicion by the examining physician. Decreased reflexes (Hypo-reflexia) is typically a sign of cauda equina compression, while spasticity (hyper-reflexia), suggests spinal cord compression, necessitating an evaluation of the cervical and thoracic spine. MRI is the diagnostic study of choice. Surgical decompression is warranted on an emergent basis if a compressive etiology is identified. Epidural Hematoma: Rarely, thoracic and low back pain may be caused be an epidural hematoma. The clinical presentation of a hematoma may mimic a disc herniation, and the lesion functions much the way an epidural abscess does - the expanding collection of fluid compresses and eventually compromises the nerves or spinal cord at that level. This produces back and leg pain symptoms early on, but progresses to weakness and paralysis if untreated. The hematoma can progress much more rapidly, however, and there are no symptoms of fever or infection to provide a warning. Because epidural hematomas most often occur following spine surgery or in patients receiving anticoagulation therapy, your doctor's level of suspicion should be heightened in these patients. Patients with motor deficits (weakness) or urinary retention need emergent surgical decompression of the hematoma. Summary:

These uncommon spinal disorders are not likely to play a role in your common back pain problem, and persistence of low back pain or leg pain associated with a recognized disc herniation or spinal disorder does not suggest that there is "something else" going on. The work-up involved in making a good diagnosis of a known lumbar spine disorder will typically rule out any of these more ominous problems right from the start. However, if you have pain that doesn't seem typical of a lumbar spinal problem, and which hasn't been fully evaluated by a careful medical work-up, then it may be to your benefit to see a specialist to get a complete assessment and a clean bill of health! The evaluation and identification of even the most dangerous causes of back pain is more a matter of careful medical evaluation – taking a good history and performing a careful exam - than of specialized spinal knowledge or testing. So, getting a careful exam from your doctor is the right place to start. After that, it's important to remember that our most fundamental imaging studies for back pain problems - x-ray and MRI - are very good at revealing or ruling out many of these most concerning disorders. Incorporated into a comprehensive work-up for atypical back pain, our modern imaging and diagnostic laboratory tools can help identify even the most uncommon problems and get us started on the right treatment path without delay. I hope you've found this discussion interesting and informative. Please share with friends and others who may benefit, comment if you have other questions you'd like to see addressed, and follow me on Facebook for announcements of other blog posts in the future. Thanks for reading!

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Details

AuthorI'm Dr. Rob McLain. I've been taking care of back and neck pain patients for more than 30 years. I'm a spine surgeon. But one of my most important jobs is... Archives

January 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed